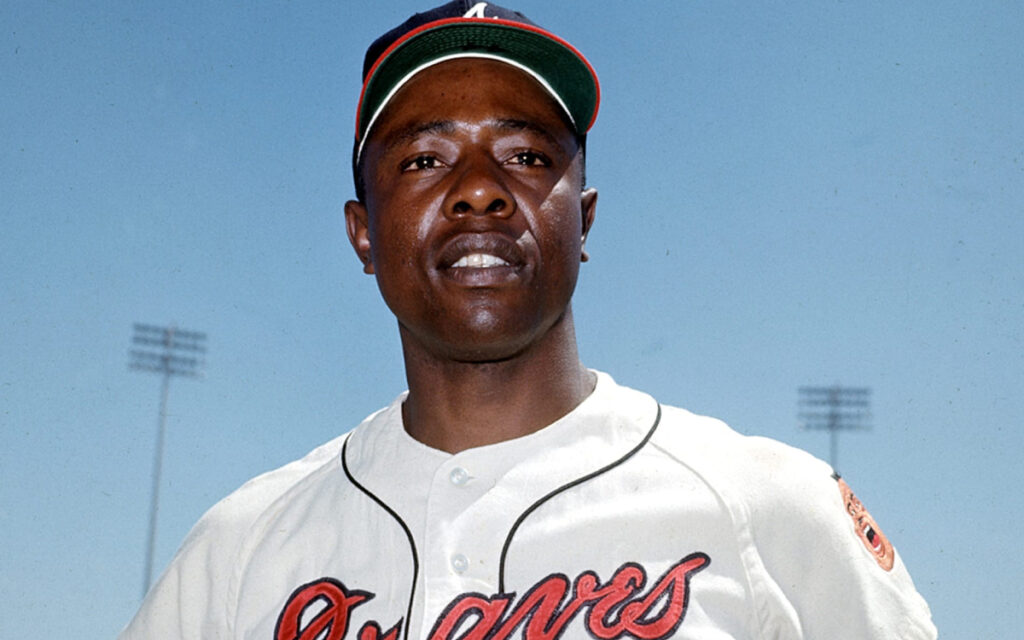

Looking back over the decades, understanding what Aaron faced seems surreal. Pictured: Hank Aaron. Photo Credit: MLB.

After facing death threats, racist catcalls, and unbearable pressure, on the evening of April 8, 1974, Henry Aaron broke baseball’s most majestic record when he hit his 715th career home run to pass Babe Ruth’s long-standing 714. As the 50th anniversary of the event approaches, a retrospect of the era and what it meant for “Hammerin’ Hank” to overtake Ruth deserves consideration.

Legendary broadcaster Vin Scully prepared well for the moment, responding to Aaron’s historic homer with the following commentary: “A Black man is getting a standing ovation in the Deep South for breaking a record of an all-time baseball idol. What a marvelous moment for baseball. What a marvelous moment for Atlanta and the state of Georgia. What a marvelous moment for the country and the world.”

He added: “And it is a great moment for all of us, particularly Henry Aaron, who was met at home plate by not only every member of the Braves, but by his father and mother.”

The previous season, Aaron, born in the Deep South, had begun the campaign with 673 home runs. Sitting only 41 homers behind Ruth, the likelihood of him eclipsing Ruth’s magical mark had the earmarks of inevitability. Aaron had just turned 39 but would have time to pass Ruth if he maintained serviceable numbers. Aaron not only did that, but he also shocked the sporting world by almost chasing Ruth down in 1973, hitting his 40th home run in the second last game of the season.

Looking to tie Ruth or surpass him in the final game, Aaron, who hit .301 for the year, had a good day. He had three hits, all singles. The pursuit would have to wait. “I feel relieved it’s over for a while,” he told reporters after the game. “Now, I just want to get lost for a few days, go fishing, and forget about baseball and the chase.”

Looking back over the decades, understanding what Aaron faced seems surreal. In a time when race gets used to guilt people for grievances their ancestors committed, Aaron could recall a time when people not only behaved with racial hatred but had the law on their side. When Aaron broke into the Majors in 1954, segregation existed, Jim Crow laws were in full force, and Aaron had memories of his 1953 season in Jacksonville, Florida, where he had to stay in separate hotel facilities and receive taunts from white fans in all the towns where the team played. Playing in Milwaukee until 1965, Aaron did not face southern crowds or their ugly racist practices. The Braves announced their move to Atlanta in 1966, and Aaron admitted to mixed feelings. He was unsure what the move might bring, but he never anticipated he would be the man to overtake Babe Ruth’s most celebrated record.

Looking back to the ‘73 season and the chase, Aaron told William C. Rhoden of the New York Times in 1994: “My kids had to live like they were in prison because of kidnap threats, and I had to live like a pig in a slaughter camp. I had to duck. I had to go out the back door of the ballparks. I had to have a police escort with me all the time. I was getting threatening letters every single day. All these things have put a bad taste in my mouth, and it won’t go away. They carved a piece of my heart away.”

To further substantiate this, Aaron had written in his 1991 autobiography, I Had a Hammer: “The Ruth chase should have been the greatest period of my life, and it was the worst. I couldn’t believe there was so much hatred in people. It’s something I’m still trying to get over, and maybe I never will.”

Aaron never forgot his roots in Negro Baseball. He knew he had overcome long odds to become a big leaguer. Aaron could never have anticipated facing down the ghost of Babe Ruth in a sport that viewed Ruth as a god. Ruth’s records surpassed imagination when he played. In 1920, the “Big Fella” hit 54 homers, almost three times as many home runs as the next player. Statistically, he overwhelmed the sport. He hit more homers than any team in the American League, more than any National League team save the Phillies, with 64.

In 1921, the Babe bested his record to 59 dingers and outperformed over half of the Major League teams. Bob Meusel hit 24 homers to finish second. When he died in 1948, the nation grieved him like a president, with a send-off not seen since FDR’s death three years earlier. When Aaron snook up on the sacred 714, Ruth fans survived. Ruth’s teammates still collected Major League paychecks as scouts or coaches. None of them found it easy to watch Ruth’s record fall, but Aaron displayed the character and confidence that drew admirers across the country.

The shattering of this all-time great’s record stunned millions. As the chase progressed, I remember getting caught up in it myself. Reading the Toronto Daily Star each afternoon became a fixture. As I remember it, the paper concocted a horse race graphic with Aaron catching up to Ruth each time he homered. Soon, many people voiced excitement about the accomplishment. I never gave much thought to Aaron being a black man. I liked the way he hit homers and he shared the same first name as my dad.

Sports has usually served as an equalizer. Most fans long ago overcame the blatant racism that Jackie Robinson braved, choosing to cheer for their teams over the colour of a player’s skin. When Scully spoke, millions watched the nationally broadcast game. There were over 53,000 fans in attendance for a team that had a hard time drawing fans. Racial divides still exist, but as in 1974, when looking for signs of less division, greater commonality, and a sense of solidarity, sports do a better job of uniting us than any other cultural phenomenon. For that reason alone, Aaron’s 715th, fifty years ago this April resonates.

Dave Redekop is a retired elementary resource teacher who worked part-time at the St. Catharines Courthouse as a Registrar until being appointed Executive Director at Redeemer Bible Church in October 2023. He has worked on political campaigns since high school and attended university in South Carolina for five years, earning a Master’s in American History with a specialization in Civil Rights. Dave loves reading biographies.