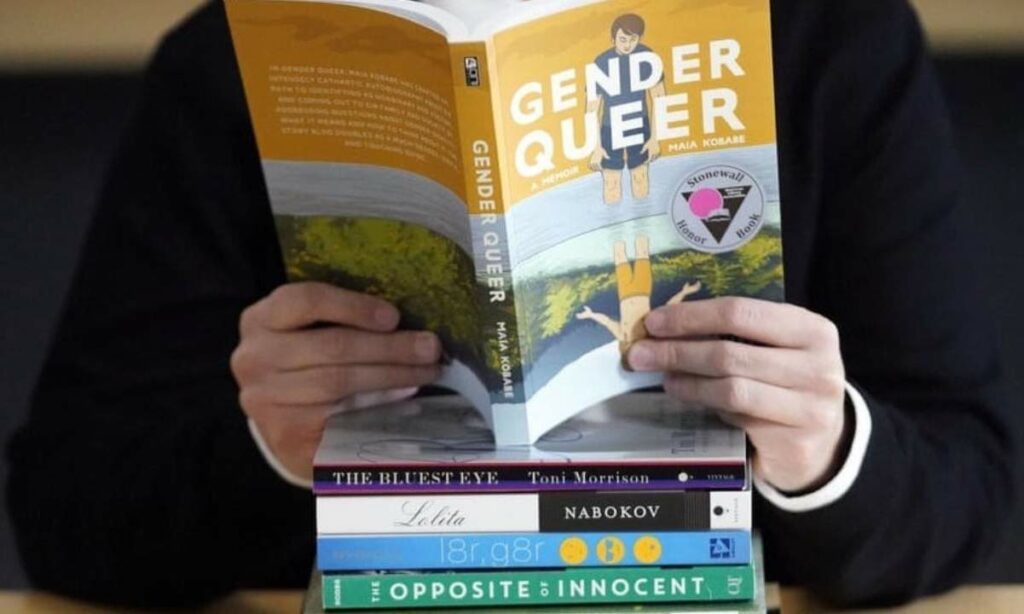

Not all book bans are created equal. There’s a difference between keeping sexually explicit material out of the hands of elementary school children and banishing classic novels from the classroom which, depending on one’s perspective, may contain uncomfortable themes or inclusions upon complete removal from their historical and cultural context. Photo credit: AP/Rick Bowmer

In a recent column, I wrote about the value of a personal library. I hold few values dearer than access to books, ideas, thoughts, and written documents. I treasure the right to read books that reflect the cultural period of any civilization. It seems evident that this enlightens our ability to process what has happened and how we can compare movements or events today with what happened in the past.

For reasons associated with protecting young minds, a movement began to evolve at the end of the last century to remove from or challenge books in certain public squares to ensure that repugnant ideas be extinguished or at least, marginalized.

Interestingly, many of the books these censors worked to withdraw from shelves tended to be classics like Huckleberry Finn, Tom Sawyer, Catcher in the Rye, The Grapes of Wrath, The Great Gatsby, and The Lord of the Flies, amongst a host of others. These books tended to be objected to in high school settings where some parents found the material too full of sexual content, excessive foul language, or racist themes. In the case of Harper Lee’s classic To Kill a Mockingbird, for example, the book allegedly did “psychological damage to the positive integration process” and “represents institutionalized racism under the guise of good literature.”

These pursuits are regrettable in a variety of ways but should not be confused with what the Left is presently calling book banning in some Red states.

While classics continue to be banned, a movement to change the wording in other long-time admired works like Roald Dahl’s stories has also gained momentum on the Left. The danger of these precedents differs from a school saying a book does not belong in its library because the content supersedes the age or processing capacity of a child.

Offending language tends to be in the eyes of the beholder. What offends one may not offend another based on belief and experience. Showing sensitivity to these issues seems wise, but basing all decisions on them can lead to misguided decisions.

We do know a lot about the mind of a child, and it should not be confused with that of an adult. The incentive to remove adult-themed books with sexual content far exceeding the appropriateness of an elementary school does not seem like the same thing as banning classic novels because a group does not like the historical references or wording. One could argue that too great a cost comes with the initiation of book bans, but then why do schools not have pornographic magazines available, or allow ShareWord (formerly Gideons) to pass out free bibles anymore? Obviously, restrictions apply when it comes to kids, free speech, and the contents in a book.

This takes us to removal of certain books from Florida school libraries and the accusation that Governor Ron DeSantis, presently thinking about running for president, promotes culture wars for political gain and sees opportunism in the withdrawal of certain books from public schools in his state.

As Education Week’s Mark Walsh reported as far back as December 2021, “The press conference last week started with DeSantis playing a video containing excerpts from graphic novels based on real experiences—such as Flamer by Mike Curato and GenderQueer by Maia Kobabe, sex education books such as Let’s talk about it: The Teen’s Guide to Sex, Relationships, and Being a Human (A Graphic Novel) by Erika Moen and Matthew Nolan, and Milk and Honey, a collection of poems by Rupi Kaur.” No one would mistake these books for writing gems that possess timeless themes. Their purpose lay in propagating an agenda, especially one fit for the times in which we live.

Each of these books have merit as written expressions of ideas, feelings, or experiences that potentially marginalized groups have encountered in society. Whether they should be content in elementary or high schools largely depends on what committees decide in each jurisdiction. If a school librarian makes the decision on her own, or if a teacher wants to impose his views on a group of students, that seems unreasonable and untenable. A school district, however, that chooses to form a group of people with vested interests, including parents, has every right to make recommendations and include or exclude whatever book they want. This group is accountable to a larger constituency and in a democracy it seems fair to include parents in decision-making.

When I taught in Ontario public schools, we followed Circular 14 as a guideline for approved books in a classroom setting. I clearly recall studying Underground Canada for several years with my grade eight classes. When I had students of African ancestry, I spoke to them privately about whether they would be comfortable or not if we read the book. I provided them with a few options if they weren’t.

On occasion I spoke with parents. I not once ever had a parent criticize the book selections in my novel studies. Public schools reflect the general population. That does not mean that all books are okay in a public school setting whether the child is five or 15. The sophistication of the content matters. Teachers, parents, trustees, and other elected officials do have say over the materials placed in front of children or at their disposal. If parents want to educate their children about gay sex, lesbianism, transgenderism, or sexual assault those books are readily available and can be accessed at public libraries, bookstores, and online.

The idea that banning books from a school library that may be too mature for an audience belongs in the same category as banning ones that hurt someone’s feelings remains a topic of heated debate. I would not likely compare the titles listed that are missing from Florida school libraries with those that have in recent decades been abolished from blue state schools.

If we are no longer able to discern the difference between a story in an historical setting and a narrative designed to push a political agenda, then it means we have become a society of activists instead of thinkers. Activists work to do something or change something in the short term. Thinking about what they are changing and the long-term implications of such change should be important. I fear activists often overlook the durable effects of their demands.

Conservatives work to conserve a tradition, a practice, or a custom. Before changing that convention, it may be wise to consider the wider and deeper consequences. Let’s hope that the better angels of our society can work out the equilibrium between appropriate material for children and the freedom to access books.

Dave Redekop is a retired elementary resource teacher who worked part-time at the St. Catharines Courthouse as a Registrar until being appointed Executive Director at Redeemer Bible Church in October 2023. He has worked on political campaigns since high school and attended university in South Carolina for five years, earning a Master’s in American History with a specialization in Civil Rights. Dave loves reading biographies.