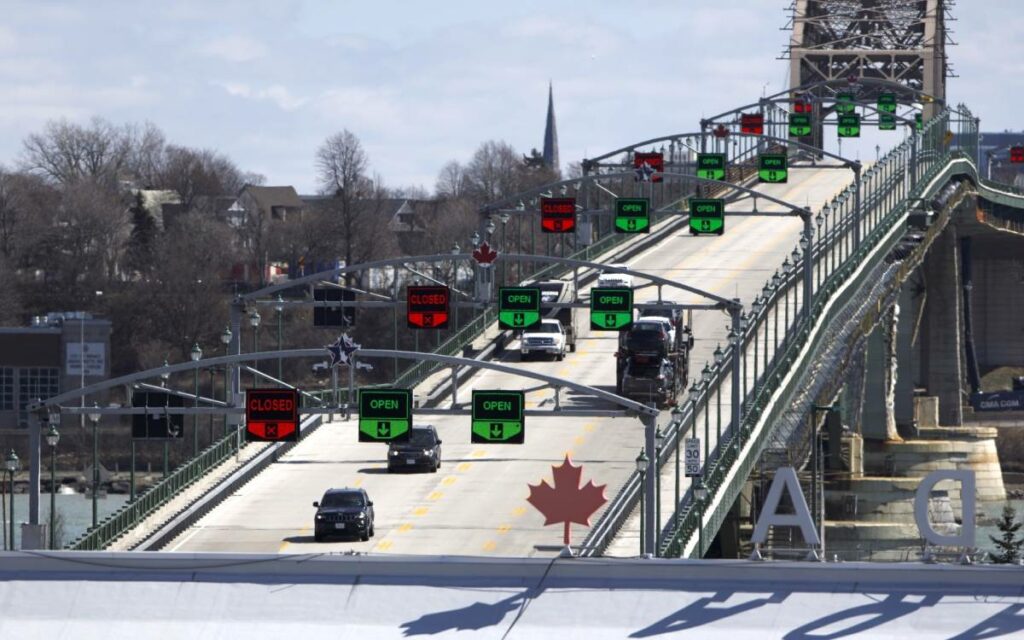

Cutline: The Peace Bridge connecting Fort Erie, Ontario and Buffalo, New York. Image taken March 21, 2020: the exact day the Canada-U.S. land border first closed to all non-essential travel. It has remained sealed ever since. However, while a far-cry from a full reopening, come July 5 fully vaccinated Canadians and permanent residents will once again be able to return to Canada from international destinations without having to quarantine. Photo credit: Bloomberg/Cole Burston

Canada hit an important vaccine milestone last week, with 75 per cent of the population having received their first dose and 20 per cent now fully vaccinated. This was coupled with news that millions more doses of both Pfizer and Moderna are destined for Canada in the next few weeks, as well as the opportunity for most Canadians to receive an accelerated second dose this summer. Vaccine hesitancy in Canada is low, and there’s been no indication that we won’t continue to meet important inoculation benchmarks.

After a spluttering spring, and while Canada’s vaccine rollout still lags behind other countries, we are on track to be farther ahead on vaccination rates than previously anticipated. But celebrating that success is difficult as policies around travel continue to be more punitive in nature than rewarding.

On Monday it was announced that the federal hotel quarantine program will wrap up July 5 for fully vaccinated Canadian travelers. Proof of a negative COVID-19 test and inoculation will be required, at least until there’s further clarity on what an official “vaccine passport” will look like. Children under 12 who are not eligible for vaccines will need to quarantine for two weeks upon arrival, making family travel extremely difficult. There’s also still no word on when foreigners, including those who are fully vaccinated, will be able to travel without restrictive quarantine measures. Meanwhile, if you’re only half-vaccinated or unvaccinated, there’s no change to the travel and quarantine rules as they currently exist.

As other countries begin to welcome international travelers without mandatory quarantine, Canada’s measures remain onerous – especially when considering cases stemming from international travel account for only about 2 per cent of COVID-19 transmission. With vaccination rates increasing globally, this number is likely to drop. The metrics Canada must meet in order to truly reopen remain elusive.

The announcement last week to keep the Canada-U.S. border closed to non-essential travel until July 21 was another example of the Trudeau government’s glacial pace on travel policy. Elected officials, businesses and citizens have raised economic and personal concerns with this protracted extension, none of which have managed to spur Ottawa to act. News over the weekend suggested that Canada would need to hit a full vaccination rate of 75 per cent before easing measures – a standard that does not seem to exist anywhere else in the world. Meanwhile, Canada’s hospitality industry continues to suffer, missing out on what for many provinces would be the busiest travel season of the year for a second year running.

The reality is that the calculation to reopen the border and allow for expanded travel involves more than vaccination rates and hospitalizations. The possibility of a federal election late summer or fall plays no small part in this thought process.

The federal government has been repeatedly criticized over its treatment of Canada’s borders, particularly by Ontario Premier Doug Ford. This has been a consistent refrain for the Ford government since the beginning of the pandemic, when they called for all international travel to be shut down in 2020 in an attempt to keep COVID at bay. Attack ads have been launched by the Ontario PCs, blaming the Trudeau Liberals for allowing variants into the province, keeping cases high in the process. Doug Ford is perfectly content to pin the province’s slow reopening on Justin Trudeau’s border choices for as long as possible.

Some may cite virus variants as a public health rationale to reopen travel slowly. The United Kingdom has been seized by the Delta variant, causing an uptick in case counts. But this is a far less indicative metric than hospitalizations and fatalities, both of which are manageable because of the UK’s vaccination efforts.

Public opinion is also on the side of keeping Canada-U.S. travel closed for longer. A recent poll from Angus Reid suggested that nearly half of Canadians would opt to keep the border closed until September, regardless of vaccination rates in either country. This has remained largely unchanged throughout the pandemic, and indicative of many people’s preference for a gradual and cautious reopening.

Simply put, the pressure for the federal government to proceed cautiously, even if out of step with the United States or other countries, is stronger than it is to act. A late-summer or early fall spike in case counts like we saw last year would leave the Trudeau government vulnerable to criticism that they opened the border too fast. Provincial governments would attempt to pin persistent restrictions on federal recklessness, rather than their own policies. The Trudeau government would not like to give any more oxygen to those Ford government attack ads by shaking up their border policies – particularly during a likely election period.

While this is a strong political rationale to maintain the status quo, it is objectively not rooted in public health considerations. Even if case counts were to rise as they have in the U.K., vaccination rates there have helped keep more citizens out of hospital and far fewer from succumbing to COVID-19. The pandemic has further exposed the fragility of Canada’s healthcare system, but barring a new variant that is resistant to the vaccine, our hospitals are back at levels that can withstand the presence of some COVID-19 cases in their facilities. Policies should be crafted with an aim to manage variants, not eliminate them altogether.

Canadians with an itch to travel, those living near the border or with loved ones on the other side of it are undoubtedly disheartened. But until Canada’s most populous province changes their tune and unless Canadians forgo their slow and steady disposition, the federal government has little incentive to change the status quo.