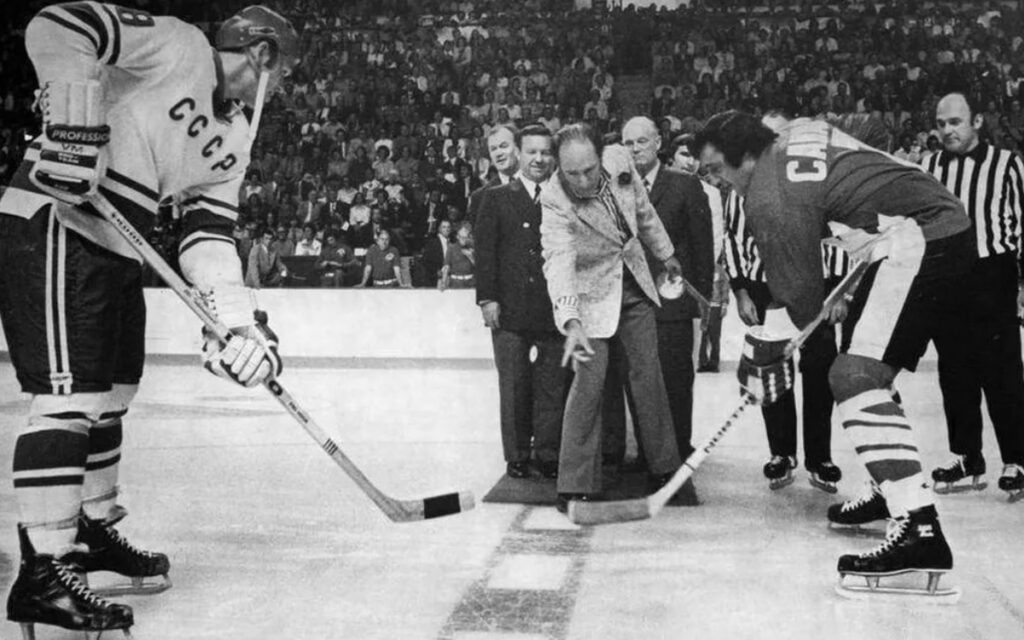

The famed eight-game hockey competition between Canada and the Soviet Union took place exactly half a century ago this month. Below describes how the binational clash came to be and chronicles the first half of the series played on Canadian soil. Pictured Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau completes the ceremonial puck-drop ahead of game one at the Montreal Forum, Sept. 2, 2022. Photo credit: The Canadian Press/Peter Bregg

When the 1972 Summit Series began, 50 years ago last week, the Cold War raged. The opposing nations sat on the brink of war. The manifestations of the conflict revealed themselves in sundry, indirect forms. Some were skirmishes on borders, others in espionage episodes, still more in contests like the famous kitchen debate between Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev and then American Vice-President Richard Nixon.

Athletic competitions also provided a forum for Cold War conflicts. Americans will always recall their controversial loss to the Soviets at the 1972 Olympics, somewhat assuaged in 1980 when the upstart American hockey team defeated the veteran Soviet club and went on to win the gold. Just weeks after the aforementioned stunner in Munich, where the Soviets grabbed gold in basketball, Soviet and Canadian hockey players gathered for an eight-game match to be played throughout the month of September.

The series attracted little interest outside of a few hockey owners, players, coaches, and fans. When Canadians of that vintage look back to their youth, however, they recall where they were when they learned about JFK’s assassination or watched Neil Armstrong walk on the moon, but for most, the one national memory they have is Paul Henderson’s goal on that long ago September afternoon. As a nine-year-old burgeoning hockey fan it turned me into a patriot and staunch anti-communist.

The series’ origin goes back to a young Canadian diplomat, Gary J. Smith, who found himself posted to Moscow in 1971. Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau desired to improve relations with the Soviet Union and Smith saw hockey as an opening. In the book Ice War Diplomat, Smith chronicles the negotiations which put the series together. While our PM envisioned a diplomatic coup that might defrost some Cold War rhetoric, build bridges, and reduce the chances of war, what happened revealed the stark differences between the Soviet world and the West. For those too young, or those who somehow ignored the national obsession it became, the intensity of this war on ice actually reflected what one might expect in a description of a field battle.

The bitterness of the rivalry accelerated quickly. Canada’s stunning loss in game one, 7-3, after an early 2-0 lead, placed pressure on Canada for game two. The Canadians were much better prepared and Peter Mahovolich, in an act only described as both heroic and stunning, ensured Canada’s victory with probably the most beautiful, if not the most famous short-handed goal in Canadian hockey history. Like a soldier behind enemy lines, the towering younger brother of the legendary Big M received a pass from Phil Esposito, proceeded to centre ice, and crossed over the blue line, deking the poor Russian defenceman (who may still be suffering from vertigo) with a fake shot, then stickhandled the puck past the Soviet goalie. The Canadian boys mobbed Mahovolich like a conquering hero who had kept the Soviet bear at bay. For now, series tied.

The series moved west after the game in Montreal and Toronto and the clashes in Winnipeg and Vancouver led to further dismay. Our boys were losing the series, and in effect, the war. While it may be hard to imagine in 2022, fifty years ago NATO countries, made up of Western Europe, Canada, and the United States faced a relentless foe in the Soviet Union. Canada held two goal leads on two occasions in game three, but the Soviets fought back each time to force a 4-4 final.

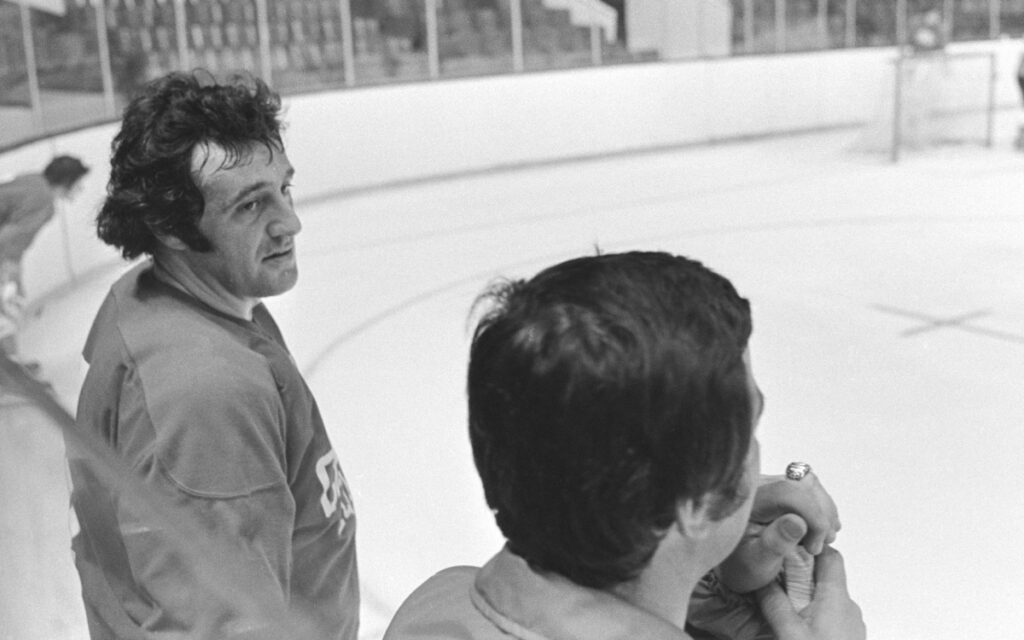

Phil Esposito, pictured beside head coach Harry Sinden in a practice at the Pacific Coliseum, was the team’s natural leader and famously rallied the troops, and the nation, before the series headed off to Moscow. Photo credit: The Canadian Press

The last game in Canada would take place in Vancouver. Canada had little excuse but to be ready. A loss would be disastrous, forcing Canada to play four games in Russia behind in the series. Unfortunately, Canada got off to a bad start, falling behind 2-0 early and the final score of 5-3 flatters the Canadian effort. Fans were incensed, booing the team off the ice. National pride took a hit. If we could not beat the Russians in hockey, with our best professionals, were we unwittingly also losing the Cold War?

In a memorable interview after the game, Phil Esposito, for all intents and purposes promoted to General, spoke on behalf of the team, delivering a stirring and patriotic speech which included the following excerpt:

To the people across Canada, we tried, we gave it our best, and to the people that boo us, geez, I’m really, all of us guys are really disheartened and we’re disillusioned, and we’re disappointed at some of the people. We cannot believe the bad press we’ve got, the booing we’ve gotten in our own buildings. If the Russians boo their players, the fans… Russians boo their players… Some of the Canadian fans—I’m not saying all of them, some of them booed us, then I’ll come back and I’ll apologize to each one of the Canadians, but I don’t think they will. I’m really, really… I’m really disappointed. I am completely disappointed. I cannot believe it. Some of our guys are really, really down in the dumps, we know, we’re trying like hell… We did it because we love our country, and not for any other reason, no other reason. They can throw the money, uh, for the pension fund out the window. They can throw anything they want out the window. We came because we love Canada. And even though we play in the United States, and we earn money in the United States, Canada is still our home, and that’s the only reason we come. And I don’t think it’s fair that we should be booed.

As a boy I remember watching this interview and one can make the case that these words, spoken with passion and earnestness, served as the first shots which began to turn the battle into Canada’s favour even as the series took a two-week hiatus. Espo had rallied the troops. He spoke from the heart and Canadians faced the reality for the first time that the stakes not only included the national game but our way of life as well.

The Soviets discipline, precision, and team-oriented style stymied the Canadians. The frustrations surfaced during the games played in Canada, but they would peak during the games played in Russia. The simmering exasperation the Canadians felt as they watched the Soviets pass crisply, employ relentless technique, and defend annoyingly well would test our boys like soldiers in war. They would be expected to enter enemy territory, decode the Red Army’s secrets, and defend the honour of a nation. The sloppiness displayed in Canada needed correcting. Foolish penalties held consequences.

Espo’s speech joined the battle and while there could be some excuse found in the Canadians not being in as good a shape, or not having developed team chemistry, these would not suffice as the series moved to Russia. First, Canada would play some exhibition games in Sweden, then on September 22 the series would resume in Moscow. During the interceding time, Vic Hadfield, Jocelyn Gouvrement, and Richard Martin would desert the team for lack of playing time. The greatest player of his generation, Bobby Orr, unable to play due to chronic knee injuries stayed with the team throughout, while many like Wayne Cashman, Gilbert Perrault, and Stan Mikita (born in Slovakia) played in just two games, suppressing their egos to fulfil supporting roles, though often starring on their own teams in the NHL.

My next column will chronicle those turbulent days in late September in Moscow.

Dave is a retired elementary resource teacher who now works part-time at the St. Catharines Courthouse as a Registrar. He has worked on political campaigns since high school and attended university in South Carolina for five years, where he earned a Master’s in American History with a specialization in Civil Rights. Dave loves reading biographies.

Dave Redekop is a retired elementary resource teacher who worked part-time at the St. Catharines Courthouse as a Registrar until being appointed Executive Director at Redeemer Bible Church in October 2023. He has worked on political campaigns since high school and attended university in South Carolina for five years, earning a Master’s in American History with a specialization in Civil Rights. Dave loves reading biographies.