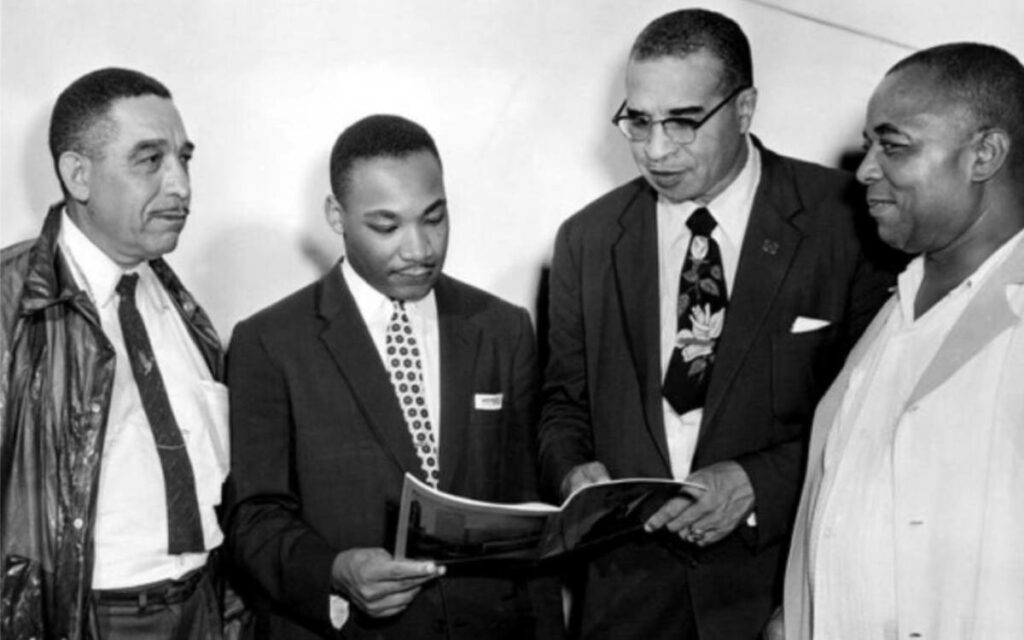

Monday doubled as the August Civic Holiday and Emancipation Day in Ontario. Pictured from left to right: Russel Small, Rev. Martin Luther King, Rev. Theodore Boone, and Walter Perry on Emancipation Day in Windsor, Ontario. August 5, 1956. Photo credit: Windsor Star Files

Since 2008, the provincial government has officially recognized August 1 as a day to celebrate the abolishment of slavery in the British Empire.

The date, which roughly coincides — and indeed, for some, represents — the August Civic Holiday, was celebrated by many in Ontario’s Black community for several decades prior to the legislative efforts of the McGuinty government.

A 1932 article in The Globe describes an early-August gathering that saw some 4,000 Black celebrants come together to mark emancipation at Lakeside Park in Port Dalhousie. A large contingent of participants travelled to the Lake Ontario south shore by steamboat from Toronto, “while hundreds [more] came from Buffalo, Niagara Falls, Hamilton and other cities.”

Only a few years later, Windsor, Ontario started holding annual festivities organized by “Mr. Emancipation” Walter Perry from 1936 to 1967. The celebrations included a parade, concerts, talent competitions, speeches, and an awards ceremony recognizing contributions to Black freedom.

People of every creed and colour from across Canada and the United States flocked to the southern Ontario city for the yearly event. At its height, the gathering attracted 200,000 visitors. Notable guests included former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and Martin Luther King Jr. The latter attended the Emancipation Day festivities in August 1956 as the event’s featured speaker.

When he travelled up to Windsor in the summer of 1956, King was in the middle of helping lead the initial campaign that would launch the 27-year-old pastor into the national spotlight: the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

Initiated in response to Rosa Park’s arrest upon refusing to give up her bus seat to a white rider, the boycott spanned from December 1955 to December 1956, with Black patrons (75 per cent of the system’s ridership) refusing to use the racially segregated city transit in Montgomery, Alabama. King helped coordinate the yearlong protest as president of the Montgomery Improvement Association and became the face of the nonviolent resistance. The protest ended when the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed a District Court decision stating that bus segregation was unconstitutional.

In the months leading up to his Emancipation Day visit to Canada, while in the thick of the Montgomery boycott, King was arrested, threatened by the KKK, and his home bombed. While no record of his speech to the Windsor crowd in August 1956 appears to exist, one can assume that his ongoing struggles with the state and society in Alabama brought a particular poignancy to his oration.

Over a decade later, in only his second-ever visit to Canada, the civil rights leader travelled to Toronto to deliver CBC’s 1967 Massey Lecture. In the centennial address, King spoke admiringly of the then-100-year-old nation.

King told listeners nationwide: “Canada is not merely a neighbor to Negroes. Deep in our history of struggle for freedom Canada was the north star. The Negro slave, denied education, de-humanized, imprisoned on cruel plantations, knew that far to the north a land existed where a fugitive slave if he survived the horrors of the journey could find freedom.”

“Heaven was the word for Canada”.

The Nobel Peace Prize-winning activist was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee less than five months later.

The preamble to Ontario’s Emancipation Day Act (2008) pays tribute to the “martyrdom” of King and acknowledges the role he played, and continues to play, in “the ongoing international struggle for human rights and freedom from repression for persons of all races”.

This article first appeared in The Niagara Independent in the context of Martin Luther King Day in January 2021. Reprinted here in slightly altered format.