As Preston Manning used to say the last time the federal deficit was so big, when you’re in a hole the first thing to do is stop digging. Very soon now, the Trudeau government needs to put down its very large shovel.

Getting Canada’s $343 billion federal deficit under control will be a daunting task. Winding down emergency program spending represents the biggest chunk of money, but, at least in theory, it is also probably the easiest to do. Temporary measures justified because the economy was closed will no longer be necessary now that it’s reopening.

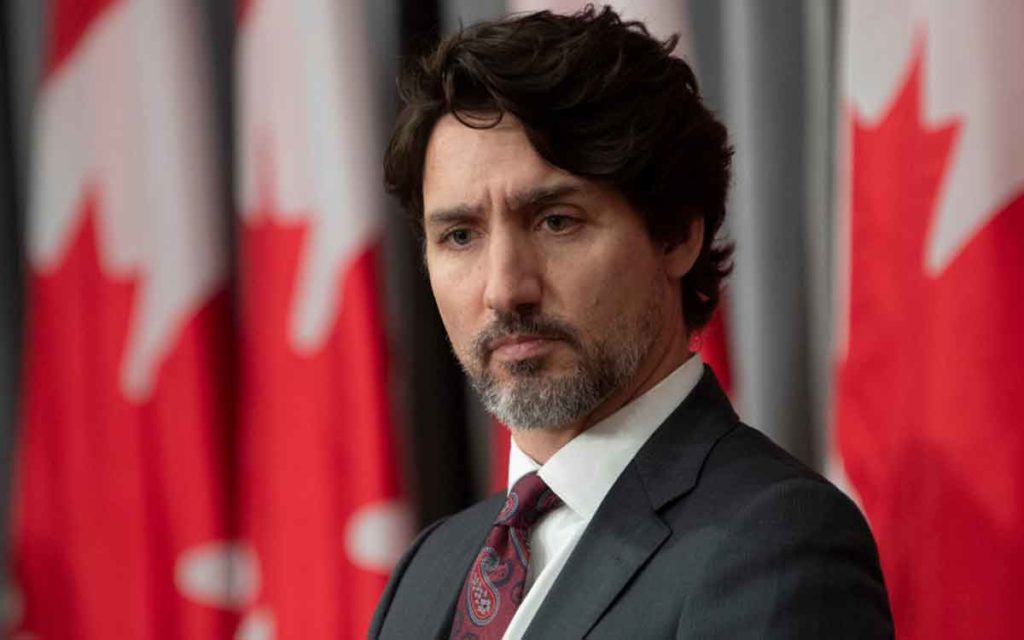

The tougher challenge for Trudeau and newly-minted Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland will be cutting into spending that is unrelated to the pandemic. It’s tougher because this government has proved either unwilling or incapable of doing so even when times were good: if the prime minister had kept his own campaign promise to balance the budget in 2019 we would have incurred around $100 billion less debt.

The collapse in tax revenues due to the economic shutdown compounds the problem, which means the government will have to really tighten its belt to avoid falling into a persistent structural deficit that is impossible to reverse.

So what can be cut?

The obvious place to look at is the largest expense. The federal government’s single biggest cost centre is the $51 billion it spends on salaries and benefits for its 368,000 employees.

Many government employees have been working hard during the pandemic and they deserve our thanks. But fully 27 per cent of federal employees took at least some (paid) leave during the pandemic, which shows that even in an emergency it’s possible for Ottawa to get by with substantially fewer people on the payroll.

The savings from a reduced headcount would be considerable: if the government were to reduce its workforce by about 15 per cent and also reduce the salaries and benefits of remaining employees by an average of 15 per cent, it could save Canadian taxpayers around $14 billion a year.

Some will protest that this seems cruel and unfair. But is it unreasonable to ask government to cut costs when many businesses have gone bankrupt and millions of Canadians have lost their jobs or taken pay cuts? Are we really “all in this together” if those whose salaries are paid by taxpayers are completely insulated from the economic impact of the pandemic—with all the pain borne by those outside government?

Politicians themselves should be no exception. If MPs and senators took a 20 per cent pay cut, they would save taxpayers $16 million a year and demonstrate in a concrete way that they are willing to walk the walk. If the prime minister of New Zealand and politicians in India and Japan can do it, why can’t Canadian politicians?

Beyond slimming down its payroll, there are plenty more places for the federal government to cut costs.

Axing corporate welfare and regional development would save nearly $4 billion a year. A one-quarter reduction in transfers to Crown corporations (including the CBC, Canada Post and the Canada Council for the Arts) would save $2.5 billion, while cutting back foreign affairs spending by the same ratio would save $1.3 billion. Taking a long, hard look at departments and agencies that lie outside core government functions—from Canadian Heritage to the National Capital Commission to Telefilm Canada—could save hundreds of millions, if not billions more.

There is simply no getting around the fact that significant spending cuts will need to be a major part of eventually getting the federal books back to balance. The longer we wait to take up the task, the greater the risk that interest rates will rise and send the cost of servicing our debt through the roof. The Trudeau government needs to channel its inner Paul Martin, stiffen its spine, and start making tough choices.

Aaron Wudrick is the Federal Director for Canadian Taxpayers Federation. A lawyer by training, Aaron practised litigation in his native Kitchener, Ontario, and then corporate law with a major international law firm in London, Hong Kong and Abu Dhabi, before returning to Canada to work with a prominent political consulting firm.

Aaron holds a BA in economics and political science from the University of Waterloo, and a J.D. from the Faculty of Law at the University of Western Ontario, where he served as student body president during his final year of studies. He lives in Ottawa with his wife and children.