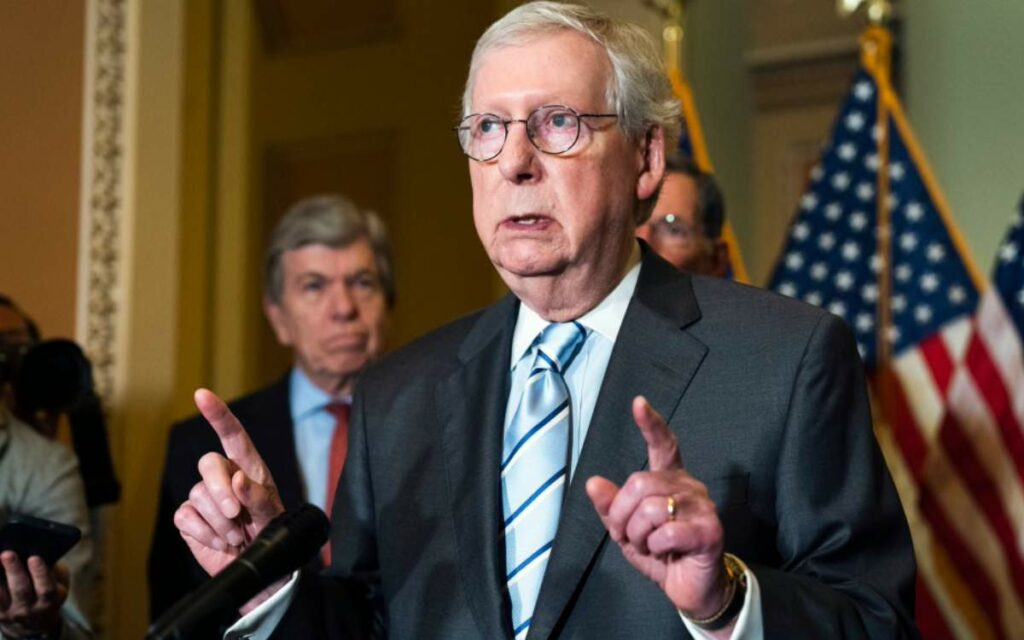

Once highly respected on both sides of the aisle, the Republican Senate Minority Leader from Kentucky now finds himself the target of censure from red and blue forces alike. Photo credit: AP/Manuel Balce Ceneta

No politician in Washington today stirs up more aggravation than the long-time senior senator from Kentucky, Mitch McConnell. Despite being hated on the left, the Republican McConnell engenders deep feelings of resentment on the right.

First elected in the Reagan landslide of 1984, Addison Mitchell McConnell III presently leads the 49 Republican senators who constitute the GOP’s caucus in the 118th Congress, a job he has held in both minority and majority roles since 2006. Explaining these split feelings about McConnell requires a deep dive into the unsavoury partisanship dividing Washington today.

When McConnell took over as Republican senate leader, the party had just lost the midterm election cycle badly and faced the prospect of a long-term position as the minority party. Building on the gradual momentum of the Tea Party movement and coinciding with the end of six years of a Democratic presidency, the GOP took control of the Senate in 2015 and McConnell became Majority Leader.

Having earned a reputation as a pragmatic moderate for much of his early career in the Senate, McConnell had Democratic friends, enjoyed respect from both sides, and comfortably reflected the times. Bipartisan legislation, working across the aisle, and delivering government services took precedence over more factional issues before McConnell joined the leadership.

Once Barack Obama assumed the presidency, and especially in his second term, the nation split apart on ideas that once united it. Whereas Obama had inspired the hope of a nation healed, his presidency seemed, for many, an homage to progressive principles and advancing changes in family structure and American cultural life that most conservatives and those on the right rejected.

Political survival demanded McConnell move to the right. For his political viability, he saw no choice. The Republican party’s drift to the right became earnest. Picked up in the undertow, McConnell soon found new ground further right than he had ever been in his life and farther out of the mainstream than he ever anticipated being.

With the 2016 election cycle ahead, McConnell seemed to expect the party to nominate someone safe, someone who could carry the moderate right agenda to a solid victory and possibly hold the White House for two terms. McConnell likely hoped that a Jeb Bush or Chris Christie presidency might give him a chance to retire as leader after helping his party’s president complete two successful terms.

Probably against his instincts, McConnell endorsed his fellow Kentucky senator, Rand Paul, for the 2016 Republican nomination. When Paul withdrew, McConnell endorsed Donald Trump on May 4, 2016, though everyone now knows he held a lot of misgivings about Trump and undoubtedly abhorred Trump’s behaviour.

Before endorsing Trump, McConnell had already infuriated Democrats when he refused to hold hearings for Merrick Garland, who Obama had nominated to fill the Supreme Court vacancy created when Antonin Scalia died suddenly on February 13, 2016. His open support for Trump, not unexpected, still upped the disdain the Dems felt toward McConnell and justified their distrust, disgust, and dismay about his role as Senate leader.

From that time forward, the Democratic Party in all its forms has held Senator Mitch McConnell in the same regard that Julius Caesar held Brutus in those last twinkling moments of life. Democrats no longer saw him as one they could work with, much less trust. To them, exacting revenge upon his denial of a Supreme Court seat to a mainline liberal like Garland became an all-encompassing preoccupation. His endorsement of Trump merely sealed their verdict.

With McConnell as the Democrats’ number one enemy, ensuring Trump, who many on the left dismissed as a populist at best, from getting anywhere near the White House seemed like an easy task. Winning enough Senate seats to take control of the upper chamber, securing the confirmation of Hilary Clinton’s agenda (including the filling of the empty SCOTUS seat), and stripping McConnell of his office as Majority Leader remained the heavy lift in 2016.

A funny thing happened on the way to the White House for Hilary Clinton and the Democrats, however, and Donald Trump became president. Appointing Neil Gorsuch to fill Scalia’s long empty seat became a top priority for the new president and with the Republican Senate numbers holding steady at 52 after the election, McConnell would be needed to guide the nomination through the Senate. Once he accomplished that, instead of the partnership stabilizing, it entered troubled waters.

Trump and McConnell’s uneasy relationship endured many ups and downs, but when Trump lost to Joe Biden in November 2020, the Democrats also took the Senate and Charles Schumer, Senator from New York, became Majority Leader. Whatever remained of the Trump-McConnell relationship dissolved at that point.

Despite McConnell’s shepherding of not only Gorsuch, but Bret Kavanaugh in 2018 and Amy Coney Barrett in 2020 to the two seats opened after first David Kennedy’s retirement, then Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death, McConnell’s unwillingness to back the 45th president’s claim of a stolen election slashed the tattered thread holding everything together.

McConnell, unlike Trump, faced the prospects of having to defend an already controversial decision to forego his principle of no Supreme Court appointments in a presidential year, a rule that had served as justification for denying a vote on Garland. Now he would insist on an up or down vote on Ms. Coney Barrett in the middle of a presidential election to replace a justice of the opposite philosophy.

Reasonable people understand the challenges of electoral politics. Being a political animal, Mitch McConnell responded predictably. Having used his political capital, with the election decided and the senate dependent on the two run-offs in Georgia in December 2020, McConnell wearily viewed Trump’s charges regarding election fraud but surveyed with greater dismay his actions. It became clear with the losses of the two seats in Georgia that Trump had little interest in preserving Republicans in Washington and much greater interest in pushing a narrative about election fraud to safeguard his reputation. Trump could not countenance the idea of being considered a loser and his machinations already included another run in 2024.

McConnell knew that without evidence the story had no legs. Later, when Trump forces rioted at the Capital, McConnell wished to distance himself further. He had defended Trump during his first impeachment trial and withstood great criticism for his total coordination with White House counsel during the proceeding.

In the second trial, held after Trump left office, McConnell voted to acquit the former president because he thought impeaching someone out of office was unconstitutional, stating in the Republican Leader’s news release of February 13, 2021, “Article II, Section 4 must have force. It tells us the President, Vice President, and civil officers may be impeached and convicted. Donald Trump is no longer the president.”

Nonetheless, in the same document he condemned the ex-president’s actions, saying, “Former President Trump’s actions preceding the riot were a disgraceful dereliction of duty … There is no question that President Trump is practically and morally responsible for provoking the events of that day … If President Trump were still in office, I would have carefully considered whether the House managers proved their specific charge.”

At this point, two large constituencies now hated McConnell. The progressive left believed him to be a craven tool of the hard right while the Trump forces on the right saw red rage over his reluctance to back their hero in his fight to expose election fraud.

That brings us to 2023. McConnell, now 81, remains as Minority Leader after a disappointing mid-term election result which saw the Republicans lose one seat and fall to 49 in the Senate. Still, McConnell sought and won re-election as leader, defeating his fellow Florida colleague, Rick Scott, 37-10 in an intra-party vote.

Since January, in the new Congress, McConnell has used his authority to enforce party discipline, removing from leadership roles those he believes are brewing trouble for the GOP. Unlike the mess in the House, where loose cannons from all directions go off message and create problems for House Speaker McCarthy, the experienced hand of Mitch McConnell just keeps the trains running on time and provides the kind of opposition that prevents Democrats from getting their legislation through easily or quickly.

McConnell’s support and so-called “obsession” with the Ukrainian War most aggravates the right these days. Writing in The Federalist, Shawn Fleetwood asserts, “With a faltering economy, a wide open southern border, imminent national security threats from the Chinese government, and radical leftists trying to co-opt unsuspecting kids into their social movements, the United States under the ‘leadership’ of President Joe Biden is in a tailspin. So naturally, out-of-touch swamp creatures such as Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell felt it was appropriate to remind us, plebs, about what’s important: Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine.”

Fleetwood and those of like mind believe that too much time, attention, and money is being spent on a far-away war while unnecessary suffering at home remains unattended. The border crisis, the importing of drugs, and ignored societal issues should be addressed before more money flows to Ukraine, say these folk. McConnell’s blue and yellow ties and consistent message, “defeating the Russians in Ukraine is the single most important event going on in the world right now,” chafes those in the nationalist or America First camp.

How long McConnell can continue this juggling act remains to be seen, but so far, his foils on the right and left have not been able to upset his act or rain on his parade. At this rate, the senator from Kentucky may yet leave office on his own terms and whistle past a political graveyard his opponents from both sides have been digging far too prematurely.

Dave Redekop is a retired elementary resource teacher who now works part-time at the St. Catharines Courthouse as a Registrar. He has worked on political campaigns since high school and attended university in South Carolina for five years, where he earned a Master’s in American History with a specialization in Civil Rights. Dave loves reading biographies.