Canadian soldiers tend to the burial of a fallen comrade. Credit: Canadian War Museum.

“That heaven might heal the world, they gave.

Their earth-born dreams to deck the grave.”

– Marjorie Pickthall (Marching Men)

Sunday marks the centenary anniversary of the armistice that effectively ended the First World War.

Roughly 61,000 Canadians were killed serving overseas during the four-year conflict; with 172,000 more reporting injuries and ailments.

All told, depending on one’s sources, the First World War took the lives of over 16 million civilians and military personnel, and left another 22 million wounded.

For many, such a colossal loss of life is so unfathomable and difficult to put into perspective that the numbers are rendered meaningless.

The sterile succession of digits hardly invokes anything of consequence, outside of magnitude: the fear, the pain, the cold, the courage, the individuals.

Though, the reality is, real people left their families, travelled thousands of miles, confronted the most unthinkable conditions, and, in many cases, made the ultimate sacrifice.

Not all of these individuals can be found in the history books, nor are they celebrated by name every November. But, each one of these brave soldiers has a unique story.

Attestation papers, medical records, personal letters, and genealogical registers all hold tidbits of their tales.

When extracted, analyzed, and woven together, the morsels of insight these sources provide allow even the most ordinary, out-of-sight infantry soldier’s story to be heard: like the story of Private John Edward Jones.

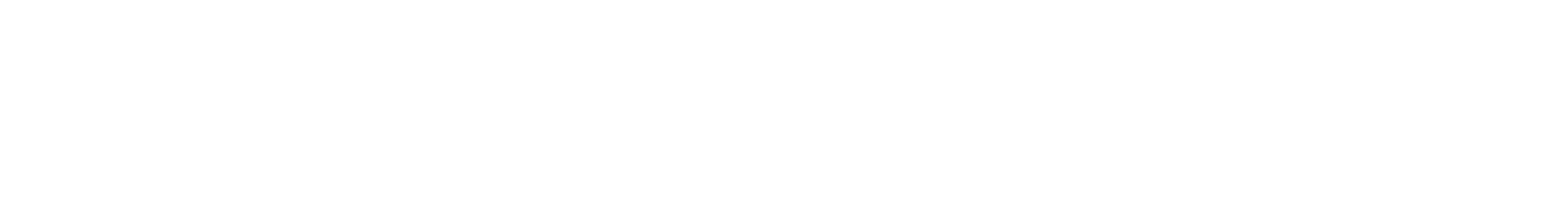

Cover of John Edward Jones’ personnel records envelope. Credit: Library and Archives Canada.

Hailing from a small village in Worcestershire, England, Jones’ parents, Emma and John Sr., married in September 1883.

Jones was born exactly six years later on September 5, 1889, only a few miles from where his parents wed.

The young Englishman probably left his home in Worcestershire as part of the “Home Children” immigration scheme. The migration plan saw some 100,000 juveniles emigrate from the British Isles to Canada between 1869 and the late 1930s.

Library and Archives Canada lists an 11-year-old “John Jones” that departed from England and arrived in Canada (destined for Toronto) in mid-1901. The entry matches Jones in name, age, and itinerary.

There is also a John Edward Jones that arrived in Ontario from England in 1909, making him 19 or 20 upon arrival.

Regardless of the exact year, it’s clear that Jones was in Canada prior to the outbreak of the war.

A carpenter by trade, Jones served one year in the 91st Regiment Canadian Highlanders sometime before 1914.

After Jones left the Hamilton-based regiment, he made his way southeast to Niagara, likely for work.

On March 11, 1916, when Jones formally enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF), he was living at 110 Maple Street in Niagara Falls.

Standing 5’ 4” tall, with a fair complexion, brown hair, and brown eyes, Jones was unexceptional in looks and below-average in stature. However, he was fit enough to serve.

Jones joined the 176th Battalion and completed some basic training at the unit’s preparation grounds on Spring Street in St. Catharines.

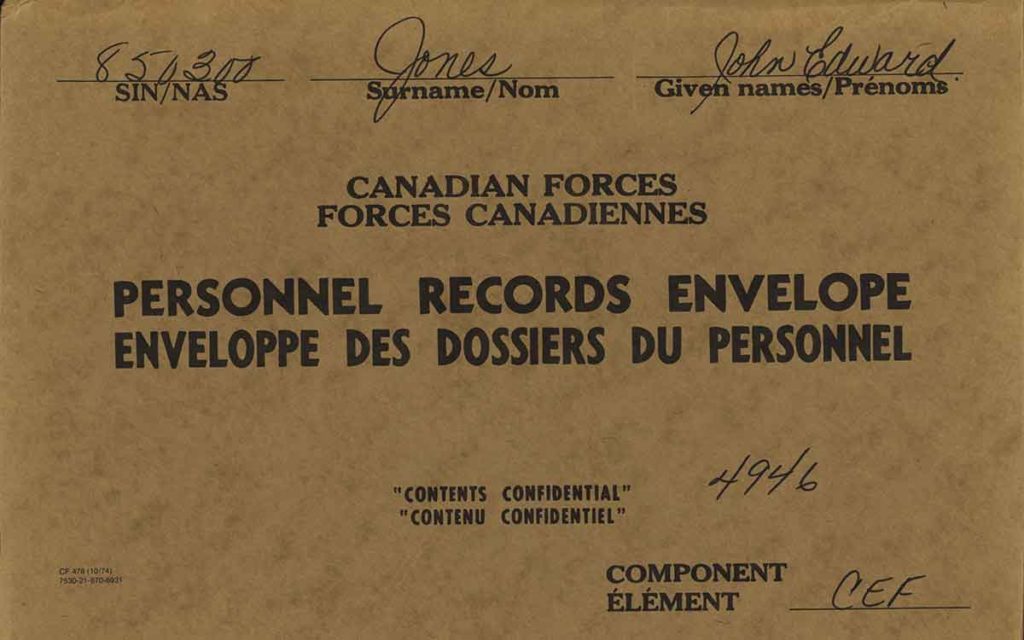

The 27-year-old, unmarried soldier left for Europe with his unit on April 24, 1917. Five days later, he embarked from the Port of Halifax on the RMS Olympic (Titanic’s sister-ship) and arrived in Liverpool on May 7.

The RMS Olympic docked in New York City in 1911. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

The RMS Olympic docked in New York City in 1911. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Two days after landing, Jones and his comrades were absorbed into the 12th Battalion.

Jones spent the next month at the East Sandling training camp near Saltwood, Kent in the south of England. At the facility, Jones and his unit would have undergone route marching and “entrenchment” training: digging trenches and rehearsing going “over the top”.

On June 4, 1917, Jones was transferred to the 164th Battalion and re-stationed at Camp Witley, about 40 miles southwest of London.

At Witley, Jones likely received some artillery training.

Like so many other soldiers looking to supplement their rations, Jones probably frequented Witley’s local canteen (a kind of commercial cafeteria). During downtime, he may have even watched or participated in one of the multiple boxing matches known to have taken place amongst Canadians at the camp.

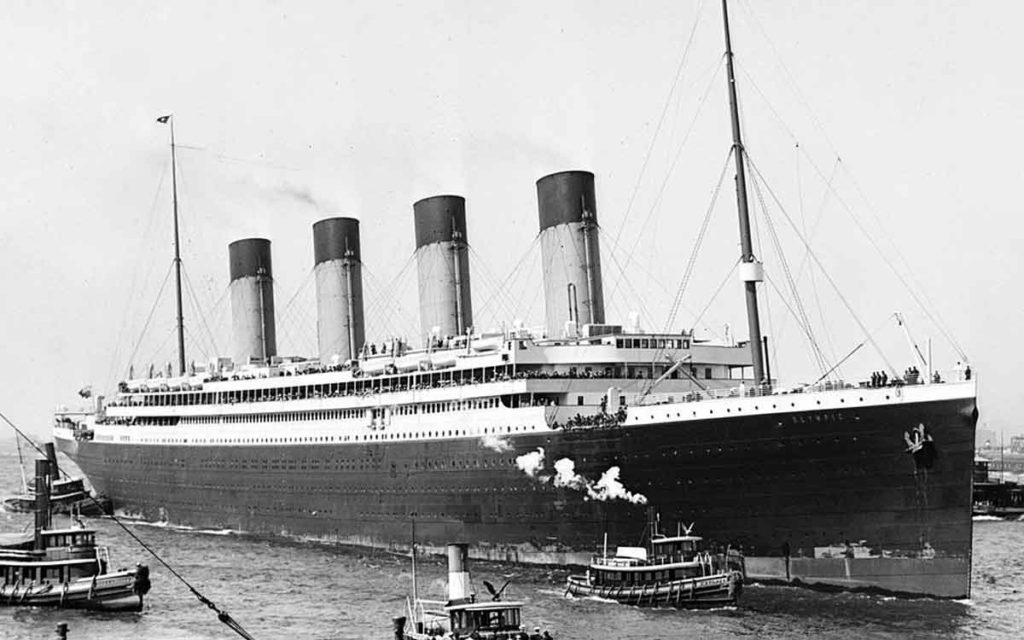

Camp Witley in Surrey, England c. 1916. Credit: Letters From World War One.

Jones spent around 10 months at Camp Witley before being transferred into the famed and still extant Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (PPCLI) regiment.

After transferring, the well-trained serviceman was swiftly deployed to France and joined his new unit in the field on April 13, 1918.

Prior to Jones’ arrival, the PPCLI participated in a number of significant battles during the First World War, including: the Somme, Vimy Ridge, and Passchendaele.

Sometime in early to mid-August, Jones suffered a non-fatal gunshot wound to the head. He may have sustained the injury at the Battle of Amiens, between August 8-11. Though, in all likelihood, he was probably shot in the aftermath of the engagement while clearing trenches and securing nearby villages around Parvillers and Damery, between August 12-15.

On August 16, Jones was admitted to No. 8 General Hospital in Rouen, about 65 miles southwest of Amiens. No. 8 General was the largest of the city’s many war hospitals.

Nurses in traditional white veil-like caps tended to Jones for over five weeks: re-bandaging and cleaning his wounds and monitoring his progress. The female medical personnel at the hospital would have been mainly British, but may have included a small contingent of the over 2 500 brave nurses that left Canada to serve overseas.

A pair of First Word War nurses help load a patient-soldier onto a train bound for England. Credit: Canadian War Museum.

On September 25, 1918, Jones was granted a three-week leave of absence to complete his recovery.

On September 27, the healing infantryman left for England. While back in his birth country, Jones likely stayed with his mother just outside of Worcester.

After a short visit and a return check-up at No. 8 General on October 21, Jones rejoined his unit in the field on November 2.

At this point in the war, the Allies were well into what would become known as the “Hundred Days Offensive”: a rapid succession of unanswered victories that saw German and Austro-Hungarian forces pushed 90 miles east from Amiens, back behind the Hindenburg Line, all the way to Mons, Belgium.

Canadian troops clearing trenches during the Battle of Amiens. The August 1918 battle kicked-off the Hundred Days Offensive. Credit: The Canadian Encyclopedia.

The Hundred Days Offensive, sometimes referred to as “Canada’s Hundred Days” – because of the significant contributions made by Canadian troops between August and November of 1918 – was the final drive that ultimately forced the Germans to surrender the war.

Jones’ regiment played at least some role in almost all of the engagements en route to Mons.

As it was the site of the first major battle between British and German forces in the war, Mons held great symbolic significance to the entire Commonwealth. After falling to the Germans in August 1914, the Belgian city never left the Central Powers’ hands for over four years.

On the morning of November 11, 1918, after months of bloodshed as part of the Hundred Days Offensive – with only hours to go until the armistice took effect at 11:00am – Canadian soldiers liberated Mons.

Some 200 Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry servicemen were among the thousands of Canadian troops who helped free the city.

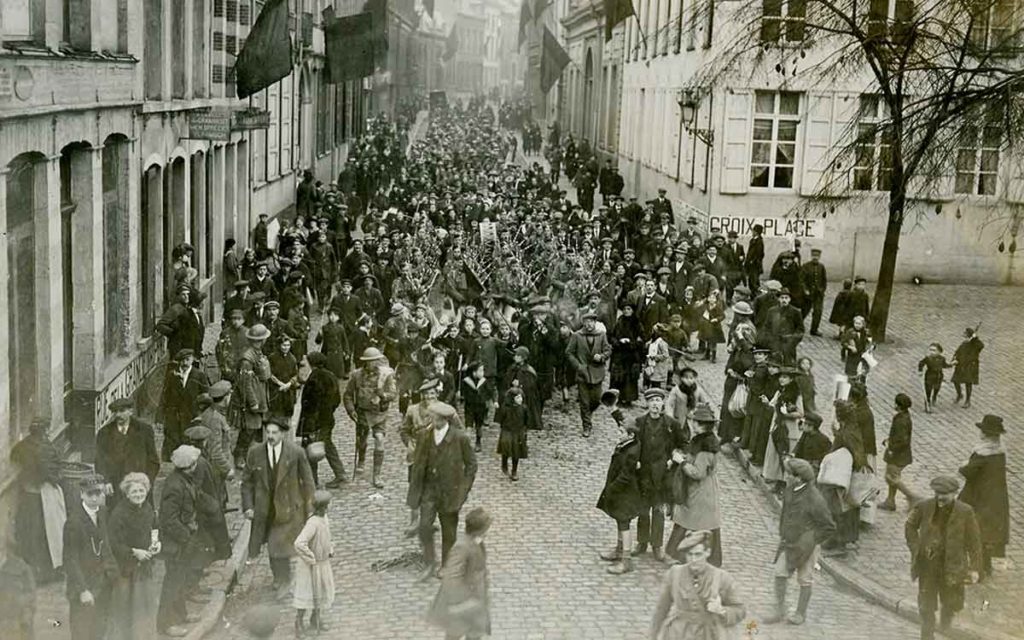

As the last German retreated, overjoyed locals and soldiers walked the cobblestone streets together, dancing and playing bagpipes.

Canadian soldiers and local citizens march the streets of Mons. Credit: Canadian War Museum.

The war was over.

However, the liberation came at a high cost.

The Allies suffered over 700,000 casualties in the final months of the war.

Counted among their number was Jones.

On November 9, 1918, two days before the war’s end, the young soldier who enlisted 30 months prior in a Niagara Falls recruitment office, was exposed to the First World War’s most sinister weapon: poison gas.

After inhaling either chlorine, phosgene, or mustard gas, Jones was transferred to the hospital, where he suffered from fatigue, fever, shortness of breath, severe chest pain, and a terrible cough.

The 29-year-old British-Canadian’s symptoms only worsened with each passing day. Finally, on November 21, 1918, Private John Edward Jones succumbed to chemically-induced broncho-pneumonia.

After travelling halfway around the world and back again, courageously serving his adopted country, surviving a gunshot wound to the head, and helping his comrades in an offensive that ultimately ended the war, Jones was laid to rest in Étaples Military Cemetery along the northern French coast.

The burial ground’s Stone of Remembrance solemnly peers across the English Channel; its gaze, fixed and confident, stretches out to the place where Jones was born.

Étaples Military Cemetery’s shelter and Stone of Remembrance. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.