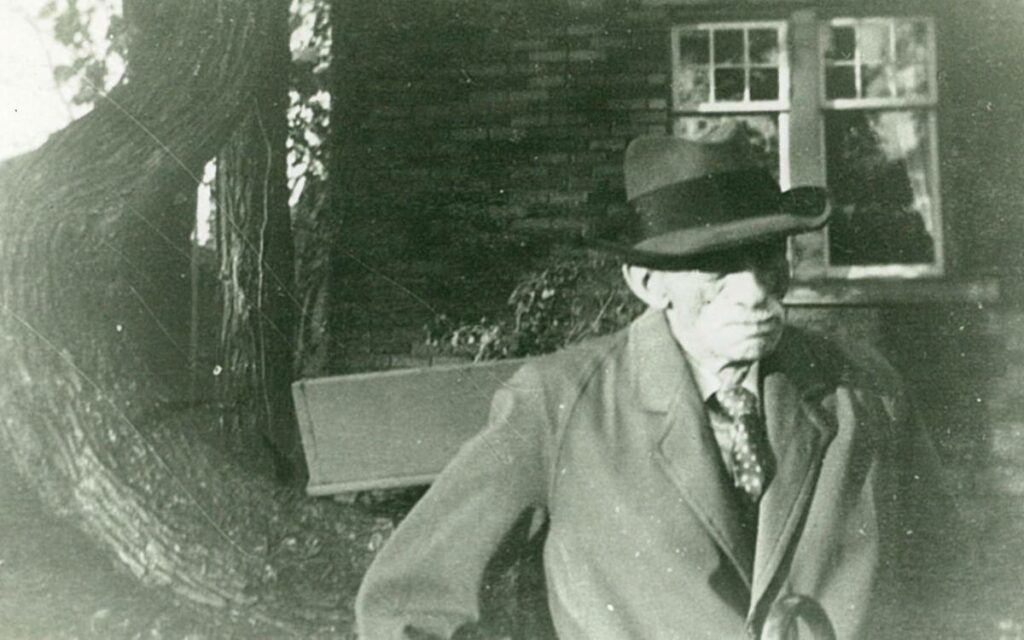

Fort Erie native Ernest Alexander ‘E.A.’ Cruikshank in Jamaica with his dog Joe, c. 1920s-30s. A prolific writer, historian, municipal administrator, and brigadier-general, Cruikshank was largely responsible for bringing the memory of Niagara’s past to the national stage in the early days of Canada’s heritage preservation movement. Photo credit: Fort Erie Public Library/Local History Archive

On May 21, 1921, exactly 100 years ago last Friday, no less than nine historic sites from Niagara were officially added to the National Historic Sites of Canada (NHSC) registry. Among the additions were Fort George, Navy Island, and the Ridgeway Battlefield.

The complete slate of Niagara sites added in 1921 constituted nearly a quarter of the country’s NHSC designations up to that point.

There were two primary reasons for the region’s healthy representation on the historic places list at such an early stage. First, and most obviously, the peninsula was home to several important events in pre-Confederation Canadian history.

Niagara served as the first seat of government for Upper Canada from 1792 to 1797, hosted a primary theatre of action during the War of 1812, and saw the last battle against a foreign enemy fought on Canadian soil during the Fenian Raids.

The second reason why Niagara was so well represented on the NHSC registry only two years after its creation in 1919 was because the inaugural chairman of the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada — the government body responsible for designating historic sites — was “one of Fort Erie’s distinguished sons”, Ernest Alexander ‘E.A.’ Cruickshank.

Born in what was then-called Bertie Township in 1853, Cruikshank was the youngest of four children. His father Alexander, a tailor and farmer by trade, and mother Margaret emigrated to Niagara from Scotland sometime in the 1830s or early 40s. According to census records, the Cruikshanks lived in a one-storey log cabin in 1851. By 1861, the family had upgraded to a two-storey brick house on Garrison Road.

The Cruikshank family home – affectionately known as ‘Maplewood’ – located on Garrison Road in Fort Erie, 1971. The house is still standing and remains in relatively good condition today. Photo credit: Fort Erie Public Library/Local History Archives

Cruikshank was educated in Fort Erie’s public school system, and later at St. Thomas Grammar School and Upper Canada College in Toronto.

It appears that the Fenian invasion, which took place just down the road from the 13-year-old Ernest in 1866, had a significant impact on the young boy. He was drawn to military life at a very early age.

After a stint as a journalist and translator in the U.S., Cruikshank joined the Niagara-based 44th Welland Battalion in 1877 as an ensign. In 1884, he was promoted to captain, working his way up to major in 1897 and lieutenant-colonel in 1899. He volunteered to fight in South Africa during the Second Boer War but, as his talents lied elsewhere, was denied the opportunity.

Officers of the 44th Welland Battalion, c. 1890s. Ernest Cruikshank is seated near center, sixth from the left. Photo credit: Fort Erie Public Library/Local History Archive

More of an administrator than a combat soldier, Cruikshank’s military career evolved in tandem with his work as a public official and historian.

In 1878, only months after first joining the Welland Battalion, Cruikshank was elected Town Reeve (equivalent to mayor) of Fort Erie. Apart from three years, he served as reeve until 1895. Throughout the 1880s and 90s he also served in a variety of roles at the county level, from warden, to justice of the peace, to clerk of the district court.

He worked as police magistrate in Niagara Falls from 1904 to 1908, while simultaneously serving as commanding officer of the 5th Infantry Brigade.

While he was moving up the ranks in the military and navigating his way through municipal politics and administration, Cruikshank was also building a reputation as a first-rate historian.

He delivered his first historical paper to the Lundy’s Lane Historical Society in 1888 and published his first major work three years later.

Cover of a pamphlet printout of one of Cruikshank’s earliest lectures delivered to the Lundy’s Lane Historical Society of Niagara Falls, 1890. Photo credit: Internet Archive/Queen’s University

Throughout his lifetime, Cruikshank published some 100 books, articles, and pamphlets. Of his myriad publications, 32 dealt directly with Cruikshank’s foremost interest as a local historian: the War of 1812.

According to University of Guelph history professor Alan Gordon, “[although] he had a national reputation, Cruikshank was primarily a local historian. His principal interest married local Niagara history and military history; but it was this attachment to home that helped him translate local Niagara sentiments into a national history of sorts.”

“Particularly through his interest in the War of 1812,” writes Gordon, “Cruikshank elevated local events into a national framework. While he never directly claimed that the battles along the Niagara frontier led to the creation of the Dominion, his writings implied that very thing.”

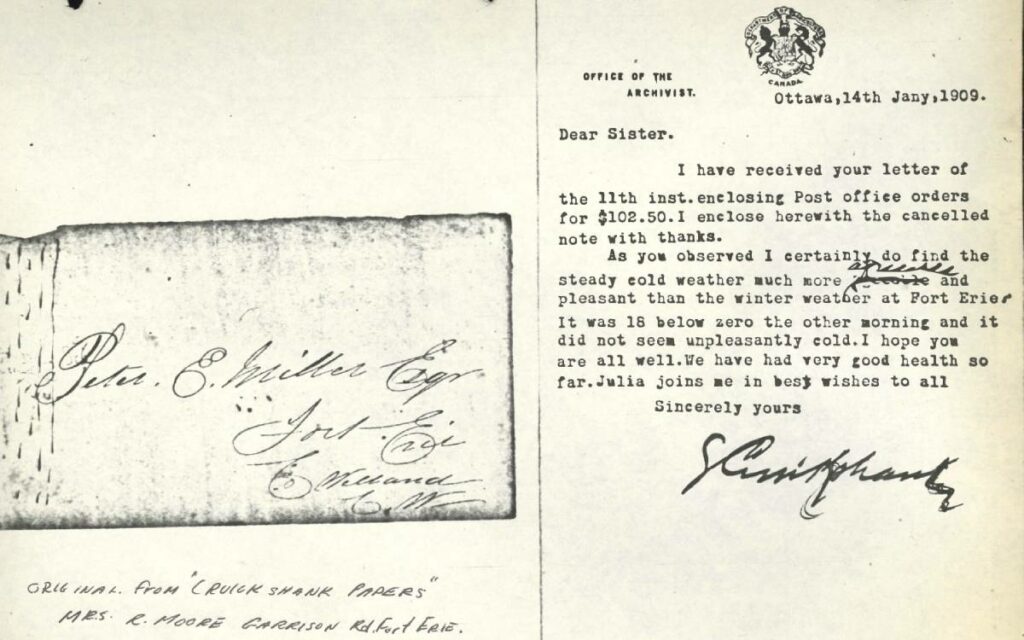

In 1908, Cruikshank left his home in Niagara to become the military’s chief archivist in Ottawa. That same year, he was elected Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada.

Copy of a letter sent from Cruikshank to his sister Rachel shortly after his move from Fort Erie to Ottawa, January 1909. Photo credit: Fort Erie Public Library/Local History Archive

Though accounts differ, by 1911 Cruikshank had moved out west to take up a permanent staff appointment as commander of Military District 13 in Calgary. Two years later, he was promoted to colonel.

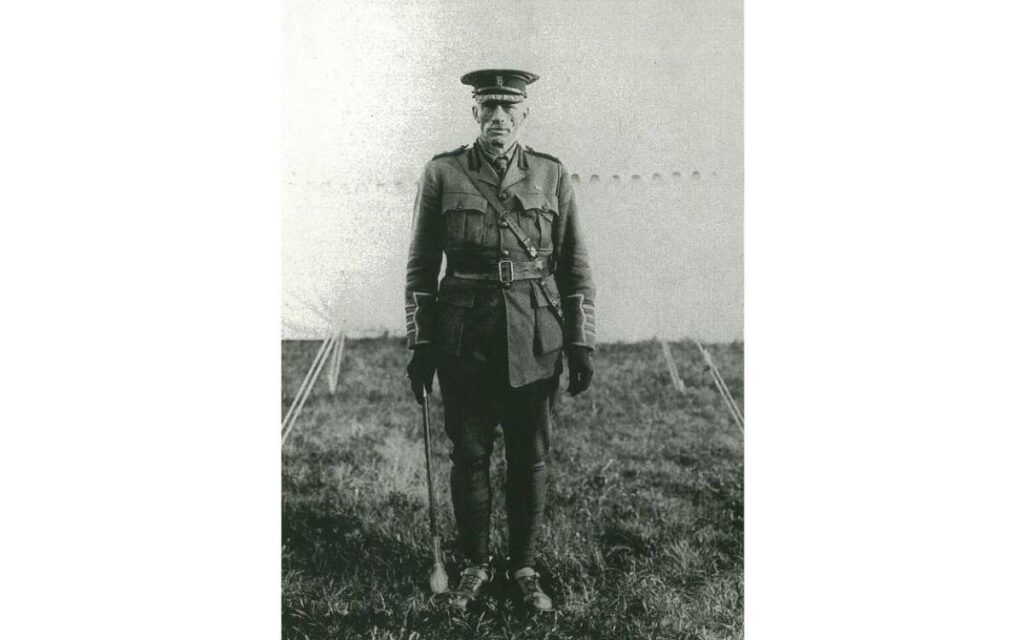

Despite having no actual combat experience, Cruikshank was elevated to brigadier-general in September of 1915. Throughout the First World War, the Fort Erie-born polymath played a large role in the country’s recruitment and training efforts. In 1917, he was posted to army headquarters in Ottawa as part of the military’s “special services”. He then spent April to August of 1918 overseas in France.

Following the war, Cruikshank became “Director of Historical Staff, General Staff” in Ottawa. It was during this time that he became chairman of the newly formed Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada (HSMBC).

Cruikshank in Calgary the year he was promoted to brigadier-general, 1915. Photo credit: Fort Erie Public Library/Local History Archive

Per Alan Gordon, during the 1920s and 30s Cruikshank was “a towering influence in the early heritage movement of Canada.”

Not only was the brigadier-general the first chairman of the HSMBC, a post he held from 1919 until the end of his life, but he was also a founding member of the Historic Landmarks Association and served as president of the Ontario Historical Society.

As Gordon argues in his 2001 book Making Public Pasts, although the HSMBC was meant to capture and consider all of Canada’s rich history, in its early years the board’s decisions were dominated by the specific interests of its members.

Hence why in 1921 — the same year that Cruikshank retired from the military to focus on historical research and writing — a total of nine sites from the Niagara native’s home region were added to the National Historic Sites of Canada list.

In all, a total of 13 local sites were placed on the NHSC registry before Cruikshank’s death — solidifying Niagara’s place in the national memory of Canada’s past.

Cruikshank (pictured near center with folded arms) standing amid the ruins of Fort Erie’s ‘Old Fort’ while dedicating a commemorative plaque, 1933. Photo credit: Fort Erie Public Library/Local History Archive

In September 1933, in one of his last visits to Niagara, Cruikshank was on hand in his former hometown to present two bronze plaques commemorating the history of the ‘Old Fort’. At the time, the site appeared nothing more than a handful of grassy hills and scattered broken stone walls.

Louis Blake Duff, former owner of the Welland Tribune, introduced Cruikshank by saying, “Here is where Brigadier-General Cruikshank began, and here, half a century ago, his historical work took shape. No man in Canada has made so large a contribution to [the] historical record. We have him here for old sake’s sake.”

In his dedicatory address, Cruikshank provided a detailed history of the Old Fort and concluded that he was “glad to think that [he had] some part in preserving” the site.

Appearing before a crowd of nearly 1,000 strong, Cruikshank spoke with fondness of his birthplace. “For me there are many pleasant reminiscences in Fort Erie,” he said. “Although a comparative stranger, I feel that I am coming home to be with you today. It may be the last occasion which I will ever be here.”

It was.

Cruikshank died at his home in Ottawa on June 23, 1939, age 85.

Just over a week after his death on July 1, the Old Fort — which sat in ruins for over a century following the War of 1812, with little appreciation for its significance until an ageing brigadier-general resurrected its history in the early 1930s — reopened to the general public following a complete reconstruction.

Cruikshank in front of his Ottawa residence, where he spent his final days, c. late 1930s. Photo credit: Fort Erie Public Library/Local History Archive