“Canadians” dotted the shorelines along Lake Ontario and the Saint Lawrence long before July 1, 1867.

That is to say, when the first British North America Act came into effect 151 years ago, a collection of insufficiently dissimilar people were already assembled under an ambiguous, though identifiable banner.

Distinctly non-American, and not entirely British (nor French), Canadians before 1867 existed in concord and conflict amongst ill-defined peers.

Seizing greater autonomy from their European progenitors and founding a formal union was not a foregone conclusion for pre-Confederation Canadians.

Tension between tongues waxed and waned. Religious incongruity brought intermittent turmoil. And disparate political loyalties created occasional bloodshed.

Though, in the end, external pressures and the myriad possibilities for growth and success outweighed any internal strife.

Comparable to the start of the Protestant Reformation or the First World War, the establishment of Canada emerged only after a lengthy succession of events culminated in a final decisive incident.

Several factors led to Confederation: the prospect of a connected rail system, the potential for economic development, Britain’s general listlessness towards her colony, and the American Civil War.

Though, much like Martin Luther’s 95 Theses and the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, a small skirmish in Niagara likely tipped the balance to create the Dominion of Canada in 1867.

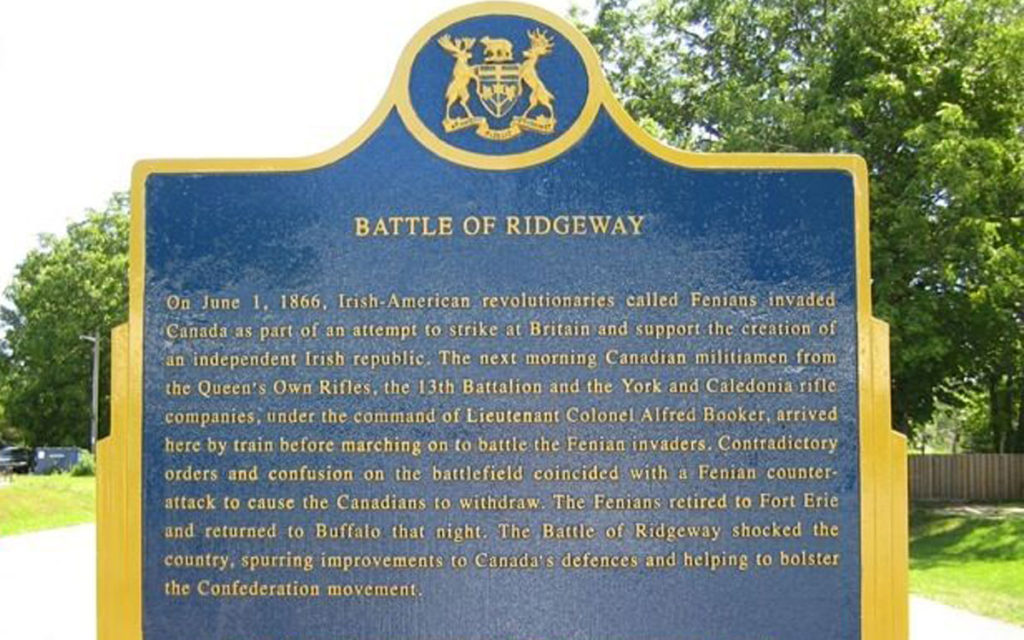

The Battle of Ridgeway, fought between Irish-Americans and Canadian militiamen in June 1866, saw hardened invaders embarrass their less-experienced counterparts from the north.

Nine Canadians were killed in action; many more were wounded, with some later dying of their injuries.

The invasion was part of the Fenian Raids, which took place between 1866-1871.

The Fenian Brotherhood, based in the United States, sought to secure Irish independence by destabilizing British interests and activity in Canada.

The Niagara incursion came only a few months before politicians left for the third and final conference to debate Confederation; where the document that sent Canada on its way to nationhood was officially drafted.

According to the great military historian C.P. Stacey, “Fenianism provided a most beneficial influence upon the immediate and ultimate fortunes of the project, by creating at once a popular apprehension of danger…and by engendering an atmosphere of patriotic enthusiasm eminently favourable to the success of an experiment in nation-building”.

In other words, the attack on Ridgeway made Canadians feel both intensely vulnerable and united at precisely the right time. The Fenian attack helped quiet anti-Confederation sentiment and arouse public interest in unification, just as politicians debated its merits.

Building on Stacey’s contention, investigative historian Peter Vronsky went so far as to name his 2011 treatment of the affair Ridgeway: The American Fenian Invasion and the Battle That Made Canada.

Similarly, Donald E. Graves thought the battle so important that the Canadian military expert included it in his 2000 book, Fighting for Canada: Seven Battles, 1758-1945.

Of course, to claim the Battle of Ridgeway, in and of itself, produced the Dominion of Canada would be a gross over-simplification.

As aforementioned, Canadian Confederation was brought about by a number of arguments, events, and accidents of history.

However, the Battle of Ridgeway played a major role in the establishment of an early Canadian identity. It also highlighted the vulnerability of remaining a collection of disconnected colonial assets in close proximity to an increasingly hostile neighbour.

The local skirmish was, conceivably, a final tipping point: an unexpected catalyst for Confederation.