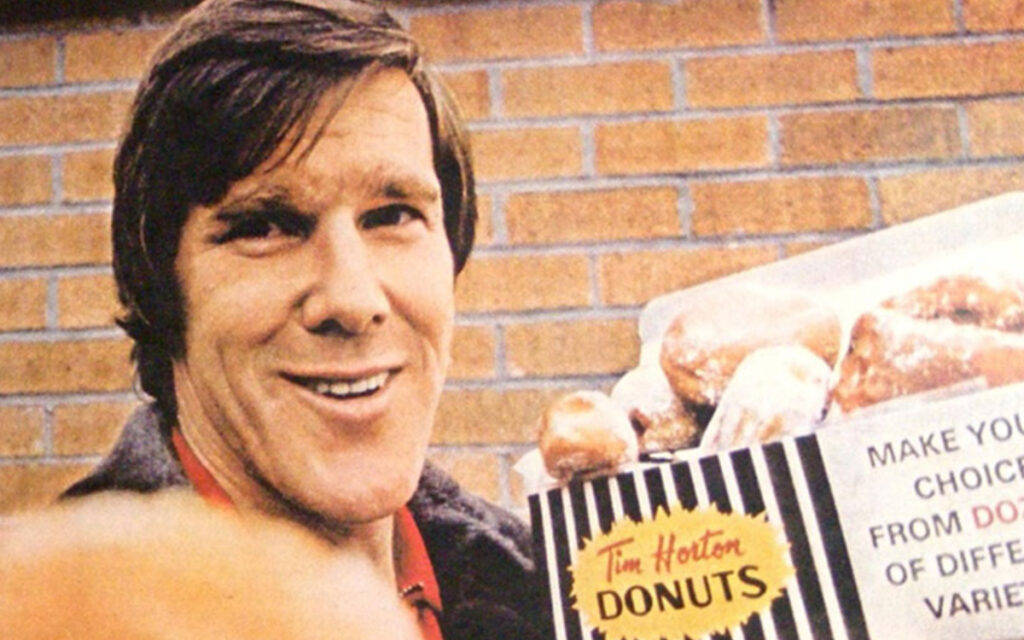

When Horton originally opened his first franchise in Hamilton in 1964, little did anyone know the empire it would become. The business is a Canadian icon, one of the nation’s best-known entities and most successful enterprises. Pictured: Tim Horton. Photo Credit: Travel Cochrane.

For millions of Canadians, the foremost daily coffee experience they prefer occurs at a Tim Hortons franchise in their neighbourhood. As of January 9, 2024, there were 3,587 Timmies (patrons preferred named) in Canada and 1,827 in Ontario. With a Timmies for every 6,100 residents, Nova Scotia holds the highest number of Timmies per person.

Of the millions of customers who visit Horton’s coffee shop every day, many, if not most, fail to realize that Tim Horton played in the NHL and, during the centennial celebration of the NHL in 2017, was ranked as one of the greatest 100 players in the history of the league.

February 21st will mark the 50th anniversary of Tim Horton’s sudden passing. Most people today know the name Tim Horton but little about the person.

In 1974, Tim Horton, at age 44, was wrapping up a Hall of Fame career with the Buffalo Sabres. Having played on four Stanley Cup winners in Toronto, Horton had bounced around after the league expanded to 12 teams, playing for the New York Rangers and Pittsburgh Penguins and then reuniting with his old coach, Punch Imlach, in Buffalo. Horton’s legendary strength, stay-at-home defensive abilities, and powerful presence characterized a twenty-four-year career.

The move to Buffalo seemed like a turn of luck when the Sabres picked him up in the intra-league draft after the 1971-72 season. Horton would return to the region where he had made his mark, be able to look after his growing company and be close to his family. With the steadying influence of Horton on the Sabre blueline in 1972-73, the Sabres, in just their third year in the league, made an impressive run to the playoffs, holding off a much more experienced Detroit club to claim the last spot in the Eastern Division. The Sabres lost to the eventual Cup champion Habs in six games, but the future looked bright.

At the start of the 1973-74 season, the Sabres looked poised to continue their rise in the standings. Convinced a playoff spot looked assured, there was talk of a Sabre run to the Cup. Many thought the Sabres could compete with the best teams in the league if they maximized their skill, youth, and veteran leadership.

They got off to a good start but faltered in November, falling behind the Maple Leafs for the last playoff spot. In the New Year, it became clear they would have to battle for a post-season place, never mind think about competing with the top teams. On February 20th, the Sabres faced a date with their rivals for the remaining seed in the spring playoffs.

Heading into Toronto, the Sabres trailed the Leafs by 7 points, but a win would close it to 5. Both teams would have 22 games left. In a tight game, the Leafs had blown a 3-0 lead and held a 3-2 edge in the last minutes. Toronto eked out a 4-2 victory with a late empty netter from Rick Kehoe. Reviewing the scoresheet on hockey-reference.com, this author remembers all the players who scored or took penalties, including Horton, who earned a two-minute minor near the end of the first period. Who knew it would be his last documented act as an NHL player?

In the morning, I awoke to my dad telling me that Horton had been killed on his way back home to Buffalo after the game. In disbelief, I heard the radio news reporter repeat the information as I tried to absorb the shock. Soon, I headed off to school at the old General Vanier Public on Torrance St. in Fort Erie. Once there, my friends and I shared the incredible developments and tried to understand what had happened.

The Toronto Star chronicled Horton’s death in its afternoon edition later that day. I remember reading the details of Horton driving his sports car and crashing at the Lake Street interchange at 4:30 am. The assumption was that he had spent the time at home with his family and headed back to Buffalo because the Sabres probably had a morning practice in preparation for their game the following night against the Atlanta Flames.

The long-time sports editor of the Star, Milt Dunnell, reported: “Michael Gula of the St. Catharines detachment of the Ontario Provincial Police, the first at the scene, said Horton’s car had flipped several times and rolled from the westbound to the eastbound lanes.” Gula also stated that the car was demolished, and Horton was thrown from the vehicle and found 123 feet away. While Gula (ironically killed in a traffic accident in 1996) had registered a faint pulse and called an ambulance, Horton was pronounced dead on arrival at the hospital.

Only later did we learn the sad truth that Horton, like many people of his era, drove drunk habitually. And at age 44, he probably needed a boost to stay up with the younger players. Glen McGregor, reporting for the Ottawa Citizen forty years later, revealed the facts, “As an autopsy obtained by the Citizen in 2005 showed, Horton was drunk. He had twice the legal limit of booze in his system. There were also indications he had been taking Dexamyl, a then-legal prescription drug that mixed dextro-amphetamine with a barbiturate.” Regardless, Horton had played well that night and earned the third star despite missing most of the third period.

After his death, the franchise, founded in 1964, took off. Sales increased, and demand skyrocketed. His widow Lori had inherited half of the franchise value when her husband died. She sold her interest in 1975 to Horton’s business partner, Ron Joyce, for a million dollars and a Cadillac El Dorado. Mrs. Horton later sued Joyce to get her half of the business returned. After losing the case, she slowly drifted from view and died of a massive coronary after Christmas dinner in 2000. One of her daughters married Joyce’s son, and they ran one of the franchises until retiring in 2023 after 37 years in business.

When Horton originally opened his first franchise in Hamilton in 1964, little did anyone know the empire it would become. The business is a Canadian icon, one of the nation’s best-known entities and most successful enterprises. Tim Horton, who came from the small Ontario town of Cochrane (about 375 km northwest of North Bay), later made a name for himself playing in some of the biggest cities in North America as a member of the legendary Toronto Maple Leafs. Horton earned a place in the Hockey Hall of Fame. His name appears four times on hockey’s holy grail, the Stanley Cup.

But 50 years after his death, on signs emblazoned, standing, and littered across Canada, the United States, and beyond, his name draws millions into the shops he founded almost sixty years ago, reminding us that some of our grandest stories begin in our smallest towns. As Pierre Berton said of Horton, “In so many ways, the story of Tim Hortons is the essential Canadian story. It is the story of success and tragedy, of big dreams in small towns, of old fashioned values and tough-fisted business, of hard work and of hockey.”

Dave Redekop is a retired elementary resource teacher who now works part-time at the St. Catharines Courthouse as a Registrar. He has worked on political campaigns since high school and attended university in South Carolina for five years, where he earned a Master’s in American History with a specialization in Civil Rights. Dave loves reading biographies.