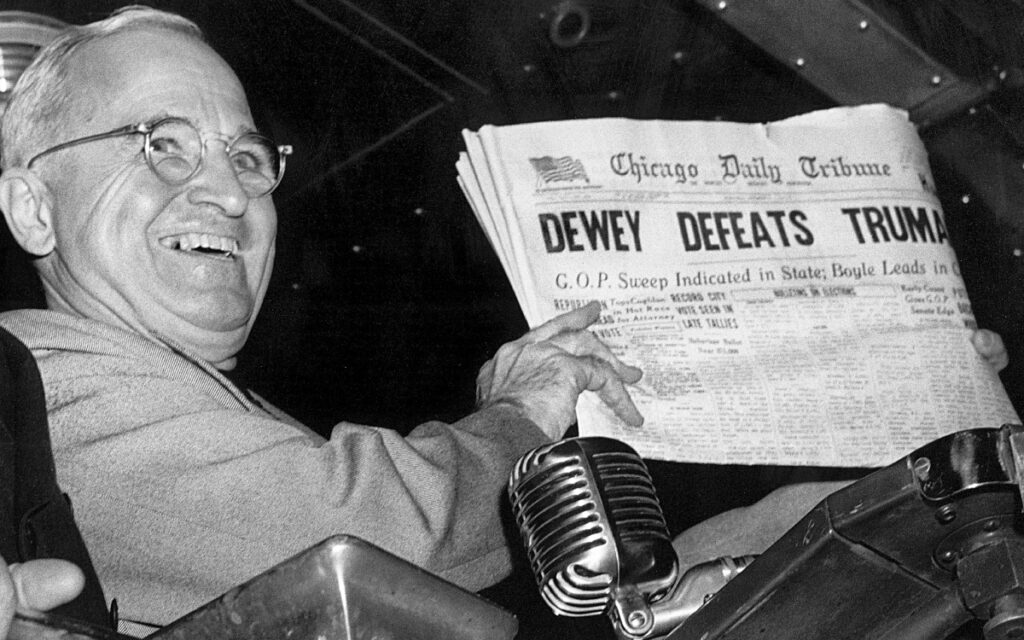

The ironic conclusion that Cohn’s piece delivers suggests that a healthy democracy in 1948 attracted four national campaigns. If American democracy entices four or more national campaigns in 2024, almost eighty years later, perhaps those anxious about the threats to democracy should acknowledge that it seems alive and well this year. Pictured: former U.S. president Harry Truman.

In a recent article for the New York Times, Nate Cohn suggested that a good comparison to the times in which we live hearkens back to post-war America. Cohn writes: “In the era of modern economic data, Harry Truman was the only president besides Joe Biden to oversee an economy with inflation over 7 percent while unemployment stayed under 4 percent and G.D.P. growth kept climbing. Voters weren’t overjoyed then, either. Instead, they saw Mr. Truman as incompetent, feared another depression and doubted their economic future, even though they were at the dawn of postwar economic prosperity.”

Cohn does not include other factors like the three major conflicts America is presently managing (Ukraine, Gaza, Iran and the Houthis) in case you have lost count. He also avoids the pandemic, global trade, and Biden’s advanced age (Truman was 64 in 1948). But comparisons are meant to make us think, not try to point out all the flaws. In fairness to Cohn, this article will analyze his thesis and attempt to provide a review.

In late 1945, the newly installed president enjoyed high approval ratings in public polls. Soldiers returning, the increased demand for goods and services, and wartime price restraints combined to drive down Truman’s ratings in the following years. As Cohn reports: “Mr. Truman’s popularity collapsed. By (the) spring in 1948, an election year, his approval rating had fallen to 36 percent, down from over 90 percent at the end of World War II. He fell behind the Republican Thomas Dewey in the early head-to-head polling. He was seen as in over his head.”

Biden did not come to the presidency when a popular war was concluding but when a very contentious pandemic was raging. Truman’s unpopularity resulted from his perceived lack of sophistication. Truman, compared to the sainted Franklin Delano Roosevelt, looked small, ineffective, and unimaginative. Biden only had to look less erratic than Trump, return governance to normal, and maintain a steady hand. Instead, he surrendered to his left flank and abandoned Afghanistan thoughtlessly, making America look weak and irresolute. Since that summer day in 2021, Russia has invaded Ukraine, Hamas attacked Israel, Iran and the Houthis have been blockading shipping routes, and China seems intent on nestling into Taiwan. Biden and Truman have little in common regarding foreign policy leading up to their re-elections.

Digging further, Cohn tries to portray an American economy on the rise without accounting for how many people remain discouraged about inflation numbers or shortages. His case suggests that Biden is undervalued, similar to Truman being unappreciated. Like many in the legacy media, Cohn thinks Americans don’t realize how good they have it under Biden’s leadership. Like those in 1948 who failed to see how much better off they were than during the Depression, people today fail to understand the great strides Biden’s America has taken since Donald Trump’s years.

Most elites (see Kim Strassel in the Wall Street Journal, January 18 – The Them-vs.-Us Election – WSJ) do not experience the budgetary challenges, grocery price shocks, or everyday financial hardships of the average citizen. Cohn belongs to the elites. As Strassel documents in an interview with JP Morgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon, the Bank executive measures up the problem: “The Democrats have done a pretty good job with the ‘deplorables’ hugging onto their bibles, and their beer and their guns. I mean, really? Could we just stop that stuff, and actually grow up, and treat other people with respect and listen to them a little bit?” Only a card-carrying member of the elite could conclude what Cohn advocates.

But the comparisons to 1948 do not end there. The election eventually included four plausible candidates. Truman and Governor Thomas Dewey of New York stood for the major parties. Governor Strom Thurmond of South Carolina headed the Dixiecrats, a Southern breakaway group from the Democratic Party, and former Vice President Henry Wallace ran on top of the Progressive ticket. Dewey still lost to the incumbent in a race with three Democratic-aligned candidates. How did Truman pull it off?

The most common explanation for Dewey’s inability to take advantage rests in the split of votes in various parts of the country that redounded to Truman’s benefit. When faced with replacing Truman, seen as a continuation of Roosevelt, Americans lacked confidence in the alternative. After sixteen years of Democratic executive rule, they needed more reason than Governor Dewey’s polite campaigning and boring speeches.

A simple switch of votes totalling less than one percent in Ohio, Illinois, and California would have given the New Yorker the victory. Truman had outworked Dewey, delivering over 200 speeches on trains crisscrossing America during the fall campaign. Does anyone believe Joe Biden has the energy to travel across America giving speeches, much less outwork former president Trump? Still, the infrastructure to divide the vote continues to expand. Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.’s independent run will draw votes from both major parties, while to Biden’s left, Congressman Dean Philips threatens to take up the No Labels ballot and drain progressive votes.

Cohn’s basic thesis asserts that Biden, like Truman, will emerge victorious because their common opponents and shared values best represent American tradition. What he fails to concede plagues the Republican Party as well. The reality is that both candidates are very flawed, carry significant baggage, are actuarially old, and have disapproval rankings that outweigh their approval standing. The cards do not suggest a repeat of the miracle of 1948, but Biden’s chances may improve if others enter the race. Statistical analyses of various states look favourable for Trump today, but a lot can happen in nine months. The more the vote gets splintered, the more likely Biden can pull off a Truman.

There is a small glimmer for Biden if he can’t win an electoral vote majority. The more candidates who enter the race, the more likely Joe Manchin will jump in on the belief that he could slip through the middle and win some states. Probably not enough to take the presidency, but enough to become a kingmaker.

If no candidate secures 270 electoral votes, the race would be tossed into the House of Representatives, creating an electoral crisis. Depending on how close a candidate stands to the magic number, there would be a lot of horse-trading. There are multiple outcomes even with a candidate-rich election. Somehow, the musing of Donald Trump’s anti-democratic tendencies looks less compelling as more entrants believe the American experiment continues and remains worth fighting for.

The ironic conclusion that Cohn’s piece delivers suggests that a healthy democracy in 1948 attracted four national campaigns. If American democracy entices four or more national campaigns in 2024, almost eighty years later, perhaps those anxious about the threats to democracy should acknowledge that it seems alive and well this year.

Dave Redekop is a retired elementary resource teacher who now works part-time at the St. Catharines Courthouse as a Registrar. He has worked on political campaigns since high school and attended university in South Carolina for five years, where he earned a Master’s in American History with a specialization in Civil Rights. Dave loves reading biographies.