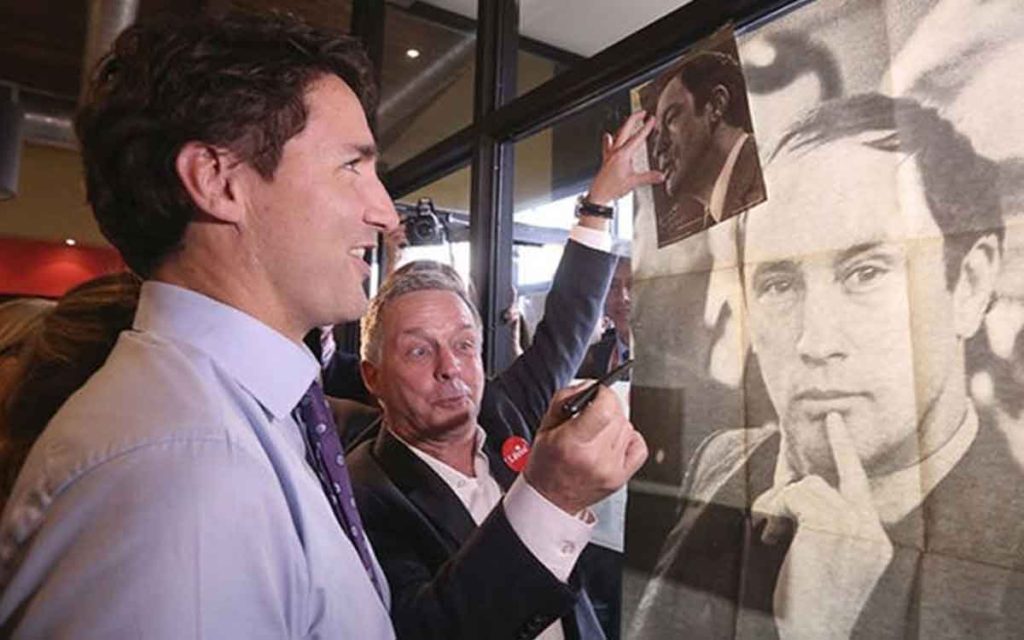

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau looks at a poster of his late father, former Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, during a campaign stop at a coffee shop in Sainte-Therese, Quebec, Oct. 15, 2015. REUTERS/Chris Wattie

Ever since his entry into politics, people have observed how different Justin Trudeau is from his father. Pierre Trudeau was one of the greatest Québec intellectuals of his generation and a university professor. Justin managed to obtain degrees in literature and teaching, but abandoned later studies in engineering and geography. Pierre was cool and reserved. Justin is emotional and demonstrative. Pierre was short, bald and pockmarked. Justin has been photographed for Vogue magazine with his equally pretty wife. Pierre did not believe in apologies for historic wrongs. Justin seems to deliver one every three months.

Despite these obvious differences, Justin has from time to time reminded Canadians that he is as much a Trudeau as a Sinclair (his mother’s family). “He [père Pierre] taught us we needed to know how to build a fire in the rain, needed to know how to portage a canoe,” he told Rolling Stone in 2017. “All these things, trying to make us as well-rounded as we possibly could be in terms of all fields of knowledge.” Like Pierre, Justin has hurled profanity at another MP on the floor of the House of Commons. Justin admired Cuba’s late dictator, Fidel Castro.

The strains of the SNC-Lavalin controversy – now in its second month – have revealed that Justin shares other aspects of Pierre’s character: defiance, stubbornness, and a reluctance to apologize. These were seen in Trudeau’s statement and news conference last Thursday, where some had expected him to apologize for how his staff and privy council clerk Michael Wernick had tried to convince then attorney general Jody Wilson-Raybould to offer a deferred prosecution agreement to SNC-Lavalin:

What has become clear through the various testimonies is that, over the past few months, there was an erosion of trust between my office – and specifically my former Principal Secretary – and the former Minister of Justice and Attorney General. I was not aware of that erosion of trust. As Prime Minister and leader of the Federal Ministry, I should have been.

So, no apology. On the contrary, Trudeau put some responsibility on Wilson-Raybould, noting that she had not come to him with any concerns: “she did not come to me, and I wish she had.” And, as Macleans’ Anne Kingston observed, Trudeau’s statement lacked his usual empathy: “He didn’t mention the human costs: the loss of two key cabinet ministers on a matter of principle or the resignation of his principal secretary Gerry Butts.”

Some thought that former principal secretary Gerald Butts’ justice committee testimony of the day before – in which he regretted the loss of trust between Wilson-Raybould and the PM – was the appetizer for a Trudeau apology. There were even leaks from the PMO that a statement of “contrition” might be coming. But Butts’ testimony was the entire meal, poisoned slightly by Michael Wernick’s testiness under questioning by committee members. Trudeau’s “erosion of trust” blather was the unwelcome bill, accompanied by a few cheap mints.

Trudeau’s admission that he should have been aware of the “erosion of trust” between him and Wilson-Raybould was as close as he got to admitting having done anything wrong. A reporter asked: “Just to clarify, are you apologizing for anything today?” Trudeau was ready for that one: “I will be making an Inuit apology later today” he said, referring to the planned apology for the government’s treatment of Inuit who had been brought south for tuberculosis treatment, before Trudeau was born. (As it turned out, poor weather grounded his flight and he could not get to Nunavut until the next day.)

“Just watch me.” Members of Parliament are “nobodies” once they are 50 yards away from Parliament Hill. “There are a lot of bleeding hearts around who just don’t like to see people with helmets and guns. All I can say is, go on and bleed.” Every boomer will recognize these as some of Pierre Trudeau’s most memorable – and arrogant – quips. Justin’s memorable quotes, on the other hand, have tended to the ridiculous: “grow the economy from the heart out” and “the budget will balance itself.”

But the stresses of governing have revealed the Pierre in Justin: shuffling Wilson-Raybould because of her resistance on SNC-Lavalin, the refusal to apologize for the relentless lobbying. Directing the Liberal-controlled justice committee to not allow Wilson-Raybould to come back and rebut the testimonies of Butts, Wernick and deputy justice minister Nathalie Drouin (though it would be interesting to hear Liberals question Wilson-Raybould and Drouin on why they held back a PMO-requested ministry report assessing the impacts of a conviction on SNC-Lavalin). Nor does Trudeau appear willing to lift the veil of cabinet confidentiality on the brief time that Wilson-Raybould served as veterans’ affairs minister.

It was Pierre Trudeau’s first-term arrogance that led to his Liberal government being reduced to a bare minority in the election of 1972 (109 seats to the PCs’ 107). He regrouped, and regained a majority in the 1974 election. If Justin is handed a minority government in October, can he govern and regain a majority like his father did? Perhaps. But he will never again be the sensitive, empathetic, feminist avatar of transparency and openness that he was in 2015. He is fully Pierre Trudeau’s son, for good or ill.

Joan Tintor is a writer and researcher. Her political experience includes having served as legislative assistant to Ontario transportation minister Al Palladini, and as a writer/researcher for the Ontario PC Caucus. She earned a degree in journalism from Ryerson Polytechnic University in 1994.